The Tribune has a piece on the American Community Survey's discouraging new numbers about poverty and middle-class incomes in the area:

The trend of increasing financial woes, dating back to the recession that began in late 2007, also includes a shrinking paycheck for those who are employed as people who were laid off from white-collar jobs take lower-paying work where they can get it. Last year the median household income in Chicago was $43,628 — $4,000 less than in 2009 and part of a steady decline over the past three years, the census figures show.

[snip]

The number of workers in 2011 who earned $25,000 to $35,000 grew by nearly 9,300 compared with 2010, according to survey estimates. Meanwhile, the number of people with annual salaries of $75,000 to $100,000 dropped by almost 4,000 during the same period.

This is consistent with stuff I've written about before: the "low-wage recovery," which is a feature of the specific sort of economic collapse the country went/is going through. But measures of poverty can be complicated, depending on what you factor in—U. of C. prof Bruce Meyer has focused much of his research on expanding the measures to include government supports like EITC and noncash benefits changes the conventional wisdom of increasing poverty. Or at least focuses on a different definition, economic well-being in comparison to income.

Translated:

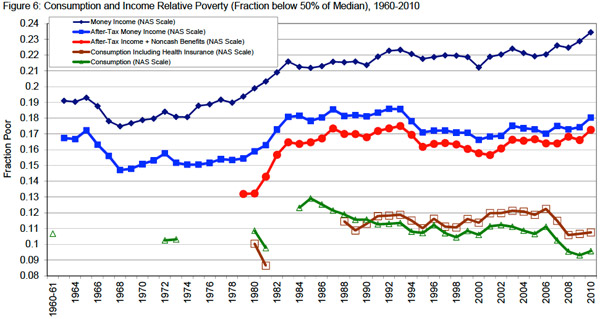

Figure 6 presents relative poverty trends for several income and consumption measures. In general, the level of consumption relative poverty is much lower than that of income relative poverty due to the lower dispersion of consumption. Unlike absolute poverty, which falls noticeably during the 1960s, relative poverty remains flat for both income and consumption based measures. Relative poverty also changes very little in the 1970s. Since then the trends are not pronounced: money income poverty has moved upward slightly, while after-tax income poverty has trended downward slightly. Consumption relative poverty has also trended downward slightly since the mid-1980s, though the measure including health insurance has been rising slowly since 2000.

The point isn't, experts agree, everything is fine, it's that "considerable progress has been made at reducing severe deprivation." Which is great, but it doesn't obviate the problem of income-relative poverty.

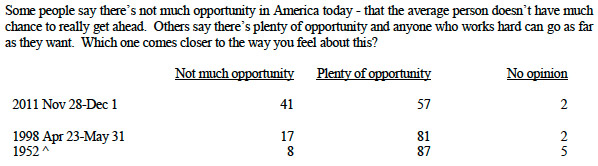

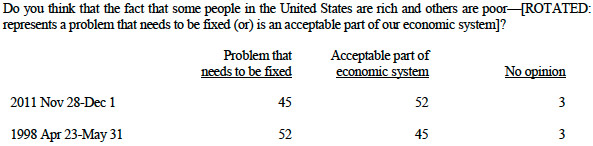

Anyway, while I was refreshing my memory on research into the different measures of poverty, I came across a remarkable poll from Gallup,conducted late last year, which asked a couple questions about income inequality and compared the answers over time.

No surprise there—middle-class jobs are giving way to low-wage jobs, unemployment is high. But this surprised me, a bit at least:

Much has been made about Mitt Romney's recently uncovered comment that "47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what… who are dependent upon government… who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you name it," and that this will hurt him a lot. My reaction is that it won't, gleaned perhaps from growing up on the outskirts of a historically poor, historically conservative, and historically government-dependent region. Being dependent on government is not the same as feeling entitled to it; in a culture that places an emphasis on self-reliance, it causes considerable tensions:

Because the government programs were the most visible, well-functioning industry in town, many locals set on them with a special brand of ire. They were helping a lot of people—more than anyone wanted to acknowledge—but they also seemed like an attack on a way of life. Sue felt the same way. “I think we’ve been helped so much,” she says, “we’re getting helped to death.” Government benefits, from welfare to Social Security to the Earned Income Tax Credit, account for 53 percent of all the [Owsley County's] income.

The most recent polling after Mother Jones obtained Romney's comments seems to bear that out. 59 percent said that Romney "unfairly dismissed almost half of Americans," but only 43 percent viewed him less favorably, and 41 percent "felt the former Massachusetts governor was making an important point about the U.S. government." The War on Poverty and the many skirmishes thereafter reduced deprevation, but as incomes decline the number of people dealing with these tensions continues to increase.