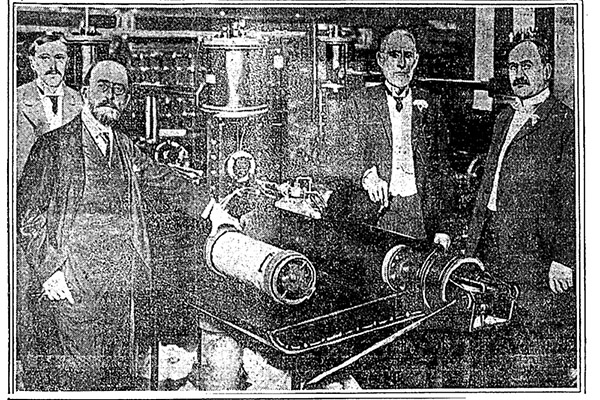

On the opening day of Chicago's nine miles of pneumatic tubes, in 1904, the postmaster and two senators celebrate the future of mail delivery—and, maybe, public transit.

There was a time when Chicagoans imagined a future filled with pneumatic tubes.

Using the power of suction, these miraculous devices were going to transport mail—and even people—around the city and suburbs. At least, that’s what the Chicago Tribune predicted in 1897. Looking ahead a century, as recently as the year 1997, the newspaper boldly asserted that pneumatic tubes “will whisk passengers from a suburb ten miles away to the heart of the town in less than five minutes.”

Well, obviously, that never happened. If you’ve seen any functioning pneumatic tubes in the last 50 years, they were probably whisking away your deposit in a bank drive-thru.

But pneumatic tubes are back in the news lately, thanks to a transportation plan floated by Telsa Motors tycoon Elon Musk. His Hyperloop isn’t exactly the same as an old-fashioned pneumatic tube, but it’s similar. Passenger pods would zip at 800 mph through a tube containing very thin air.

As The Atlantic pointed out, Musk’s scheme is a high-tech variation on an old idea. Pneumatic subways were attempted in the 1800s, and several cities—including Chicago—had functioning pneumatic tube systems to deliver mail in the early 20th century.

Chicago had nine miles of underground tubes shooting canisters filled with letters back and forth between several post offices. Like just about every other infrastructure project in those days, it raised suspicions about kickbacks and sweetheart deals. As aldermen debated whether to give a private company the deal to install and run the system, the headlines included “MAIL TUBE DEAL MADE IN SECRET” and “PROFITS IN THE CONDUITS.”

When the City Council finally passed an ordinance, it gave the deal to the Chicago Postal Pneumatic Tube Service Co. The system opened with a ceremony on Aug. 24, 1904. The first items sent through the tubes were a silk American flag and a bouquet of roses for the postmaster general.

Five months later, the post office temporarily shut down some of the tubes. “The heat from the rapid movement of the cartridges, congealing the cold air in the tubes, has produced moisture,” Chicago’s postmaster, F.E. Coyne, explained. “The dampness permeates the capsules, which are not airtight, and as a result, in spite of our precautions, some of the mail is slightly damaged.”

But a couple of years later, a national commission praised Chicago’s pneumatic tube system, saying it had improved the efficiency of mail delivery. Similar systems were operating at the time in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and St. Louis.

Officials talked about expanding Chicago’s network—the company running the system envisioned a hundred miles of tubes—but they couldn’t reach a deal to make it happen. This was a public-private infrastructure partnership (hey, does that sound familiar?), but there was friction between the partners. The company insisted that it should own the pneumatic tubes, while city officials said the tubes should eventually become the public’s property.

In 1908, Chicago inventor Joseph Stoetzel proposed a system of larger pneumatic tubes that could transport freight— and eventually, passengers—between cities. To prove his device worked, Stoetzel sent a 2,000-pound canister flying through a steel tube. And to show how safe his invention was, Stoetzel placed his young son, Robert, inside a pneumatic tube carrier, resulting in some surreal Chicago Daily News photos. According to the photo book Chicago Under Glass, the boy had one word for reporters after he served as a guinea pig during his father’s demonstration: “Whew!”

Photo: Chicago Daily News Archive

Technical World Magazine was so impressed with Stoetzel’s work that it declared: “We need large pneumatic tubes that will carry humanity wherever it cares to go as easily and safely as the mails are now carried.” But it wasn’t to be.

In the end, it was President Woodrow Wilson who killed Chicago’s pneumatic tubes. Because the tubes served the U.S. Post Office, they needed federal funding, and not everyone in Washington thought it was a good use of money. In 1918, Wilson vetoed funding for postal tubes in Chicago and other cities. He said the tubes were out of date, and that it was less expensive to transport mail by truck.

That 1897 Tribune article predicting a golden age of pneumatic tubes was looking more and more far-fetched. But another prediction in the story is finally coming true in 2013—to some extent. The article imagined that Chicago’s elevated railroad tracks would become unnecessary (thanks to all of those tubes). And so what would the city do with its L tracks? “The elevated railroad structures will be used as footways and boulevards,” the newspaper suggested.

As it turned out, Chicago still needs its L trains, but one abandoned freight line will soon become an elevated park and walking trail called The 606 (aka the Bloomingdale Trail). So those futurists of 1897 weren’t completely full of hot air.