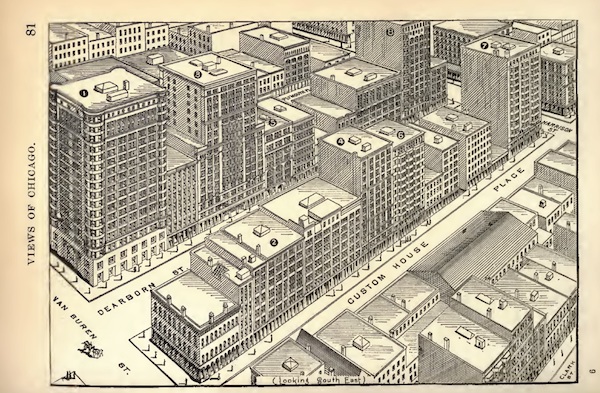

A century ago, Chicago was the publishing capital of the country. It all started when the man who changed the printing industry forever—Ottmar Merganthaler, the German inventor of the Linotype machine—moved here in 1886 and set up shop a few blocks from Dearborn Station, at the intersection of Polk and Dearborn. Over the next 30 years, the neighborhood went from vice district to Printers Row, home of book publishers like M.A. Donohue & Co., magazine and catalog printers like R.R. Donnelley and Sons, and even mapmakers like Rand McNally.

Today, you can still see the legacy of these paper giants in the neighborhood’s architecture—narrow blocks and wide windows for maximum sunlight, books hidden in the ornamentation of early Chicago School skyscrapers, and terra cotta murals depicting the history of the printing press. But after printing technology changed in the 1950s, and sprawling factory floors were needed to house automated press machines, all of the printers fled Printers Row for the suburbs.

Well, all except for one. And if it wasn’t for a single beer in 1982, they would have left, too.

Palmer Printing still stands just north of Polk and Clark, a stone’s throw from Dearborn Station (which now houses offices and retail shops). It began as E.F. Palmer and Co. during the golden age of Printers Row, when another German immigrant, Everett Palmer, opened up a small print shop in 1937. Originally housed two blocks over on Dearborn Street (in the same building where Sandmeyer’s Bookstore stands today), the company soon expanded across the alley to what’s currently known as the Printers Square Condominiums building on Federal Street, where it remained for the next four decades.

As a child, Ed Rossini made paper airplanes out of printing stock and tossed them off the fire escape of that building. “I can’t believe my dad let me climb out there,” Ed says, sitting behind his father’s old desk this spring, a few days after the Printers Row Lit Fest. Ed’s father, Ciro Rossini, started working at E.F. Palmer and Co. in the late ‘40s when he was just 18 years old, sweeping the floor and making deliveries. He didn’t learn how to use a printing press until he was drafted into the Korean War, where he ran a mobile map-making press from the back of an army van.

When Ciro returned to Chicago, he didn’t have to sweep the floor anymore. “He became a second son to Everett Palmer,” the younger Rossini says. Ciro worked the press, joined the sales team, and eventually bought the company from Palmer in the early ‘70s when Printers Row was mostly abandoned except for squatters. “It was a rough neighborhood back then,” Ed remembers. “Whenever we’d walk past a homeless guy, my dad would say, ‘There goes another printing salesman out of a job.’”

Despite being colorblind, Ciro Rossini steered Palmer Printing through the automated press revolution of the 1950s and ‘60s, the lean years of the ‘70s, and the neighborhood’s real estate boom in the ‘80s, when most of the old press buildings were converted to lofts and student housing. Eventually, Ed Rossini took over for his father in the mid-’90s, and he’s still the president to this day.

So, how did the Rossinis succeed in Printers Row when none of the other printers could?

If they’d been a larger company in the 1950s, they would have been forced to follow Rand McNally and R.R. Donnelley and Sons elsewhere. And if one of their employees hadn’t grabbed a beer one night in 1982, they’d have been priced out by the real estate boom.

“We got kicked out of that building,” Ed Rossini says from the roof of Palmer’s current headquarters, pointing at the windows across the alley he once climbed out of as a kid. “The guy who owned that complex wanted to make it apartments. He was friends with Jane Byrne, the mayor at the time, and she got the zoning changed.” After receiving eviction notices in the early ‘80s, Ed’s father was planning on moving the company to the suburbs.

“But one of our press men was at the bar next door having a beer, and the guy next to him was the security guard for this building. They got to talking, and the security guy says the bank wants to sell this building, even though there was no sign on the door yet,” Ed says. The next day, hands were shaken, the building was theirs, and Palmer Printing remained in Printers Row.

Soon after, Ed began helping his father bring the company into the digital age. “My last year of college, I came down and installed our first computer system. We had all IBMs on the administrative side, and all Macs on the creative side,” he says. Ed’s modernization plan paid off, as the desktop publishing explosion of ‘80s and ‘90s completely changed the printing industry (again), and put some of his competitors out of business.

Today, Palmer continues adapting to a changing print market. Demand waned during the mobile revolution and the recession, so Ed expanded the company’s services to include mailing and email marketing. “Printing has become more of a communication medium than a transactional medium,” Ed says, “so you have to have a multi-channel, integrated marketing campaign.” That approach has attracted some of the biggest clients in town, including BMO Harris Bank, the CTA, TD Ameritrade, Crate & Barrel, and even Pitchfork.

For now, Ed plans on remaining the last printer in Printers Row. “We love the neighborhood. It’s a nice little community, lots of dogs and families, like living in the city and the burbs at the same time.” He walks to most of his meetings in the Loop, and takes a Divvy bike anywhere further away. “Some customers come in when they don’t really need to. They just want an excuse to see the city.”