The Chicago area has produced more professional athletes than any city in the U.S. — a total of 1,061. That’s 494 football players, 387 baseball players, 155 basketball players, and 25 hockey players. Los Angeles only has 818, New York 546. We don’t have an explanation for why Chicago is the most athletic city in America, but we do have a list of the 10 best local athletes.

Red Grange, football, Wheaton

Harold Grange was the original football hero. He had the best nicknames, too: “Red,” for his hair. “The Wheaton Iceman,” because he worked on an ice truck during summer breaks from high school. In 1924, as a junior at the University of Illinois, Grange scored five touchdowns against a University of Michigan team that had won 20 games in a row. In the first 12 minutes, he returned the opening kickoff for a touchdown, then scored on rushes of 67, 56, and 44 yards. Grantland Rice, the most poetic scribe of the Golden Age of Sports, called Grange “A gray ghost thrown into the game/ That rival hands may never touch,” which inspired Grange’s most memorable sobriquet, “The Galloping Ghost.” At the time, college football, with its gentleman athletes, was more prestigious than the fledgling National Football League, made up of part-time factory rats. Bears coach George Halas thought Grange could give his new league legitimacy. The day after Grange’s last college game in 1925, Halas signed the Ghost to a $3,000-a-game contract, plus a share of the gate, making him the star attraction of a 19-city barnstorming tour. When the Bears played the Cardinals at Cubs Park, Grange drew 36,000 fans — five times the usual attendance. In a 1927 game against the New York Yankees, Grange suffered a knee injury that compromised his speed and his ability to cut, reducing him to “just another halfback.” He’s remembered as much more.

George Mikan, basketball, Joliet

The list of great Lakers centers ends with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Shaquille O’Neal, but it begins with Mikan, who played for the Lakers when they were in Minneapolis, where the team’s nickname made more sense. Six-feet-ten inches tall and bespectacled, Mikan changed basketball from a quick game controlled by scooting little guards to a power game dominated by big men in the middle. After helping DePaul win the National Invitational Tournament in 1945, Mikan turned pro, with the Chicago American Gears of the National Basketball League, a precursor to the NBA. Mikan led the league in scoring three times, and won five championships in his seven seasons. “George changed the game,” said his teammate Bud Grant, later coach of the Minnesota Vikings. “I have played with and coached many great players. But I’d have to say that George Mikan is the greatest competitor I’ve ever seen or been around in any sport.”

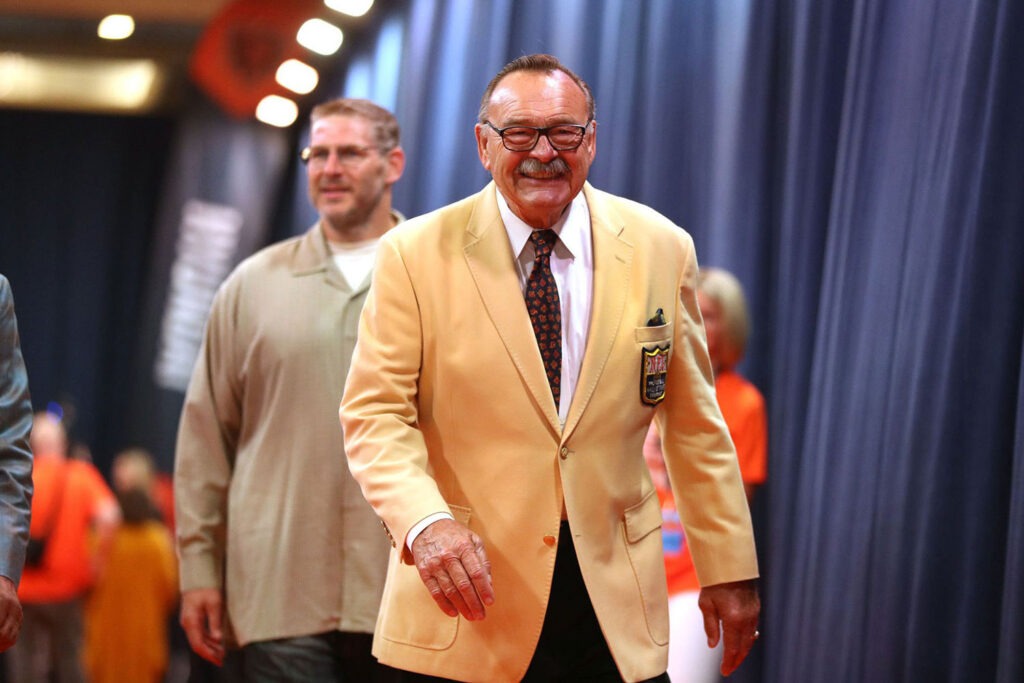

Dick Butkus, football, Chicago

Dick Butkus, who died this year, was the quintessential Chicago athlete, the only name on this list who both grew up and spent his entire career here. Butkus graduated from Chicago Vocational High School, then the University of Illinois, then was drafted by the Bears, meaning he played every home football game in his home state. Plus, his name, with its hard consonants, sounded like a Chicago epithet. “My God, the name!” wrote journalist Tom Wolfe “– a goat the size of a rhinoceros! What else could he be but the greatest middle linebacker in the history of football?” In that role, Butkus established the Bears as a team defined by great defense, which would reach its fulfillment in the 1985 Super Bowl winners, led by his successor, Mike Singletary. Butkus, unfortunately, never won a championship. In fact, in his nine years with the Bears, the team had only two winning seasons. Butkus was not to blame, because nobody played the game more intensely. “When I played pro football,” he once said, “I never set out to hurt anyone deliberately — unless it was, you know, important, like a league game or something.”

Rickey Henderson, baseball, Chicago

Is Rickey Henderson a Chicagoan? He was born in Chicago, in the back seat of an Oldsmobile on the way to a South Side hospital, the fourth child of his 19-year-old mother. “I was already fast,” he joked. “I couldn’t wait.” At age 2, Henderson left Chicago to live with his grandmother in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. When he was 7, his mother moved the family to Oakland, where Rickey would star for the Athletics. Rickey Henderson should be the left fielder on any all-time major league baseball team. He didn’t hit for average or power like Ted Williams, but he stole more bases, scored more runs, hit more leadoff home runs and — as a TV commentator once said, —“bothered more pitchers” than any player in the game’s history. Baseball statistician Bill James wrote that Henderson’s game was so complete that “if you could split him in two, you’d have two Hall of Famers.” In the words of his teammate Mitchell Page, “Rickey Henderson is a run, man. That’s it. When you see Rickey Henderson, I don’t care when, the score’s already 1-0. If he’s with you, that’s great. If he’s not, you won’t like it.” That’s what baseball is all about.

Isiah Thomas, basketball, Chicago

No Chicago athlete ever antagonized his hometown as much as Isiah Thomas. Isiah started out well enough, playing basketball at Kennicott Park in Oakland, leading St. Joseph High School in Westchester to the state finals. Then he joined the Detroit Pistons, the team that delayed Michael Jordan’s rise to dominance. As Bill Laimbeer pointed out in The Last Dance, the NBA was eager to see the torch passed from Magic Johnson and Larry Bird to Jordan as the face of the league. The Bad Boy Pistons were eager to get in the way of that. To do so, they developed a defensive scheme known as the Jordan Rules, which enabled them to defeat the Bulls in three consecutive Eastern Conference Finals. “Any time he went by you, you had to nail him,” Pistons coach Chuck Daly said. “If he was coming off a screen, nail him. We didn’t want to be dirty — I know some people thought we were — but we had to make contact and be very physical.” Thomas was less involved in containing Jordan than Bill Laimbeer and Dennis Rodman, but Jordan still had such hard feelings against the Pistons that he insisted Thomas be left off the 1992 Olympic Dream Team.

Kirby Puckett, baseball, Chicago

Puckett was raised in the Robert Taylor Homes, as one of nine children crammed into a three-room apartment. In his autobiography, I Love This Game!, he calls the South Side housing project “the place where hope dies.” But Puckett’s athletic hopes began with stickball games on the concrete walkways between the high rises, with aluminum foil bats and balls made of rolled-up socks. At Calumet High School, Puckett played third base, but not well enough to impress college scouts. After high school, he went to work installing carpeting in Ford Thunderbirds at the Torrence Avenue plant. After getting laid off, he attended a major league tryout, where he caught the eye of a coach at Bradley University in Peoria. After Puckett’s father died, he transferred to Triton College in River Grove, where he was spotted by Jim Rantz, a scout for the Minnesota Twins. “What impressed me the most was the way he carried himself on and off the field,” Rantz said. “It was like 90 degrees or more and everyone else was dragging around. He was the first one on the field and the first one off. You could see he enjoyed playing, he was having fun.” Puckett played major league baseball with the same elan, winning six gold gloves, two World Series championships, and a batting title. His .318 career average was the highest of any right-handed hitter since Joe DiMaggio. Puckett was forced to retire suddenly in 1996 when glaucoma cost him vision in his right eye. Ten years later, after packing 350 pounds on his stocky frame, he died of a stroke at age 46.

Dwyane Wade, basketball, Chicago

Wade grew up on the South Side, the son of parents who split up when he was 4 months old, and a mother whose drug addiction often landed her in jail. “Even when our mother’s own troubles took hold, getting her deeper into drugs and a relationship with an abusive boyfriend, she still did whatever she could do to keep us safe,” Wade wrote in his autobiography, A Father First. “There is no question I worried about my mother when she was out at night, and loved her so much I couldn’t sleep because I wanted her to come home and let me know she was okay. But there is also no question that Jolinda Morris Wade’s love for her children and her desire to see us achieve our dreams was the most important truth of my early years.” Wade played high school basketball at Harold L. Richards in Oak Lawn, and was recruited to Marquette, one of the few schools that would accept his low ACT scores. He led the Golden Eagles to the Final Four, then left school to enter the NBA Draft, where he was selected fifth by the Miami Heat. Wade won three championships with Miami, on the 2006 team with Shaquille O’Neal and the 2012 and 2013 teams with LeBron James. Wade, who idolized Michael Jordan, played a season with his hometown Bulls near the end of his career. He now lives in California with his wife, actress Gabrielle Union, having left Florida because its anti-LGBTQ laws discriminated against his transgender daughter.

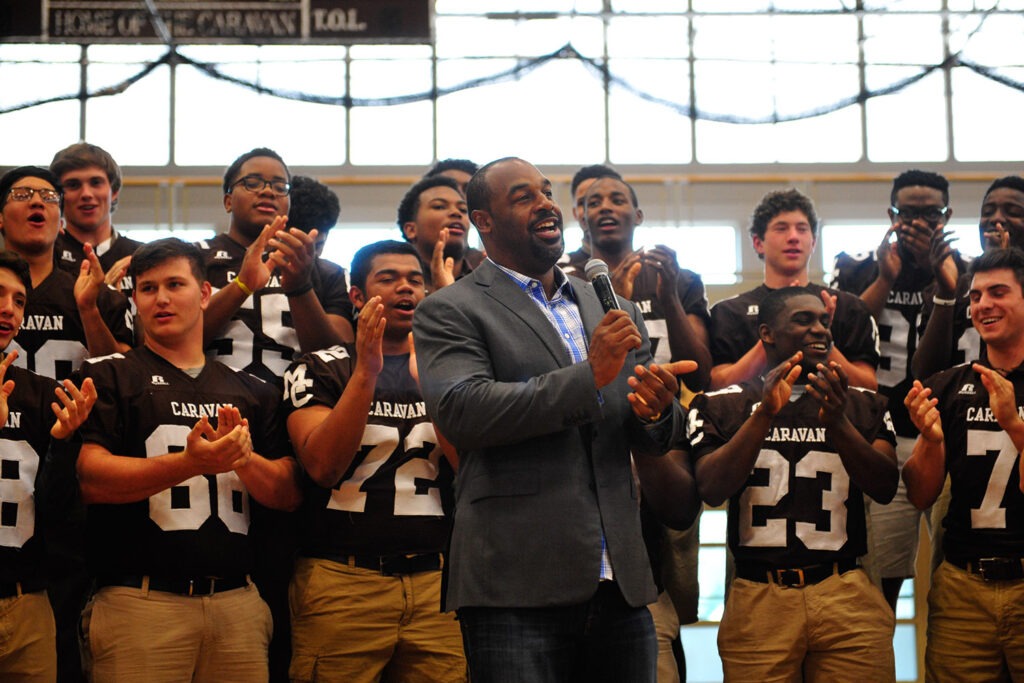

Donovan McNabb, football, Chicago

McNabb got his start as the quarterback of Chicago’s best high school football team, the Mount Carmel Caravan. As a sophomore, he was a backup quarterback when Mount Carmel defeated Wheaton Central for the 1991 state championship. (Also on that team: Simeon Rice, future defensive end for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.) McNabb later donated $250,000 to his alma mater. As a member of the Philadelphia Eagles, McNabb went to three Pro Bowls and two NFC Championship games, but ESPN commentator Rush Limbaugh still took a racially motivated shot at him: “Sorry to say this, I don’t think he’s been that good from the get-go,” Limbaugh said. “I think what we’ve had here is a little social concern in the NFL. The media has been very desirous that a black quarterback do well. There is a little hope invested in McNabb, and he got a lot of credit for the performance of this team that he didn’t deserve. The defense carried this team.” ESPN fired Limbaugh. The next season, McNabb led the Eagles to Super Bowl XXXIX, which they lost to the New England Patriots. McNabb is not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but as he told students when he presented Mount Carmel with the golden football he received at the Super Bowl, “I played in a Super Bowl. Not a lot of people can say that.”

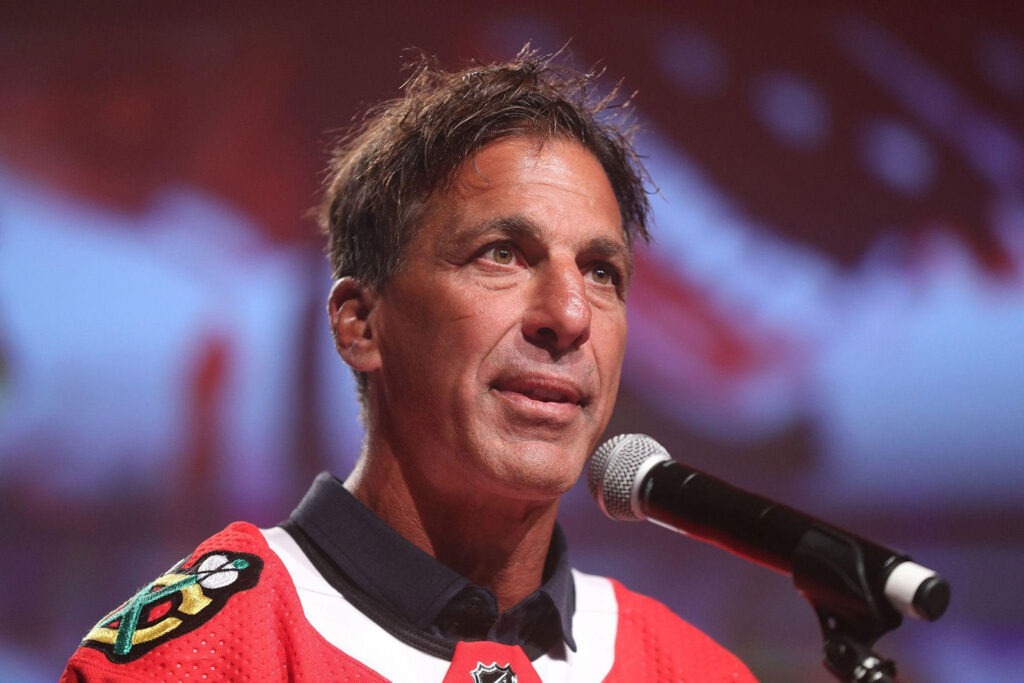

Chris Chelios, hockey, Evergreen Park

In the history of the National Hockey League, only one player was more durable than Chris Chelios: Gordie Howe, Mr. Hockey himself. From his beginnings as a 22-year-old rookie with the Montreal Canadiens, Chelios played 26 seasons, retiring as a 48-year-old defenseman with the Atlanta Thrashers, a team that did not exist when he entered the league (and no longer does). That tied Howe in seasons played, but didn’t match his 52-year-old retirement age. Chelios’s longevity was the result of intense, bizarre workouts. His favorite: riding a stationary bike in a sauna. “Most 40-year-olds would have had a heart attack and that would have been the end of them,” Detroit Red Wings general manager Ken Holland said. During his 10 seasons with the Blackhawks, Chelios often signed autographs after games at his Cheli’s Chili Bar on Madison Street. “I truly believed I was going to retire as a Blackhawk,” Chelios wrote in his autobiography, Made in America. “I had overwhelming respect for owner Bill Wirtz. I grew up watching Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita. The idea of playing anywhere but Chicago had zero appeal for me.” When Chelios was traded to the archrival Detroit Red Wings, “I felt like I’d been punched in the gut.” But he won two Stanley Cups in Detroit, and at the age of 45, became the oldest player to see his name inscribed on the trophy.

Shani Davis, speed skater, Chicago

Winter Olympic champions come from Norway, from Austria, from Russia: cold countries, with fair-skinned inhabitants. Shani Davis came from Hyde Park. He started out roller skating — a popular South Side pastime — but then his mother went to work for an attorney whose son was an elite speed skater. Shani began skating at the Robert Crown Center in Evanston, and the family moved to Rogers Park. After dominating junior competition, in 2002, Davis became the first Black speed skater to make the U.S. Olympic team. At the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, Davis won the 1,000 meters, making him the first Black athlete to win an individual medal. He held the world record in that event for 10 years. Four years later, Davis repeated as the 1,000-meter champion in Vancouver. Davis was the first Black speedskater, but not the last. In 2022, Erin Jackson won the 500 meters in Beijing. “Hopefully we’ll see more minorities, especially in the United States, get out and try these winter sports,” Jackson said. If they do, it’s because of Davis’s example.