“Bricktown? It doesn’t really ring a bell,” said Bruce Bailey Jr., a member of the family that owns The Good Old Days, an antique store on Belmont Avenue. “I might have seen it on a map once. It confused me. They used to call this Antique Row, because there were 15 antique stores. They’ve torn down so many buildings, there are only five of us left. Now it’s considered Roscoe Village.”

I had come to the corner of Belmont and Leavitt in search of an archaic neighborhood name. I’d seen “Bricktown” on Mapometer, a site I use to chart my runs. Zoom in, and in between Lake View, Logan Square, and Humboldt Park are sub-neighborhoods with much more romantic names: Bricktown, Pacific Junction, Whiskey Point.

Todd Nyenhuis, who owns Praha, an antique store across the street, rediscovered Bricktown the same way I did.

“Whenever I pull up Google Maps, it says ‘Bricktown,’” he told me. “I always tell people it’s an old-fashioned name. My neighbor at the shoe store across the street says it’s because there were brick factories. He’s been here 30 years.”

Indeed, in the 19th Century, the soil along the North Branch of the Chicago River yielded so much clay that brickyards set up nearby, to fire it into the brick that built Chicago. The Illinois Brick Company operated at Addison and Western. Once Roscoe Village became a bedroom neighborhood, though, “residents whose economic subsistence did not depend on local industries increased public objection to the noisome, ugly clay pits along the river,” according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

The brickyards shut down. The name Bricktown was forgotten — until it was programmed into internet maps, by cartographers with empty space to fill.

It’s the same story at Pacific Junction, which is now part of the Humboldt Park neighborhood. Pacific Junction is the point where Metra’s Milwaukee District North line, to Fox Lake, diverges from its Milwaukee District West Line, to Elgin. The tracks were originally owned by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific. That railroad has been defunct since 1980, but its name persists — at least on the internet. To view the junction, I climbed a graveled embankment on the north side of Wabansia Avenue. Pacific Junction would be a great spot for railfanning. A Metra train sped toward the Ogilvie Transportation Center. Across the tracks was a squat, square brick building: Metra Tower A-5, which once controlled switching operations at Pacific Junction, but has been closed since the 1990s.

On my way back down the embankment, I spotted a man watering his lawn. I asked him if he knew he lived next to Pacific Junction.

“Thirty five years living here, I didn’t know that,” he said. “I know one train goes north and the other northwest, but I didn’t know it was called Pacific Junction.”

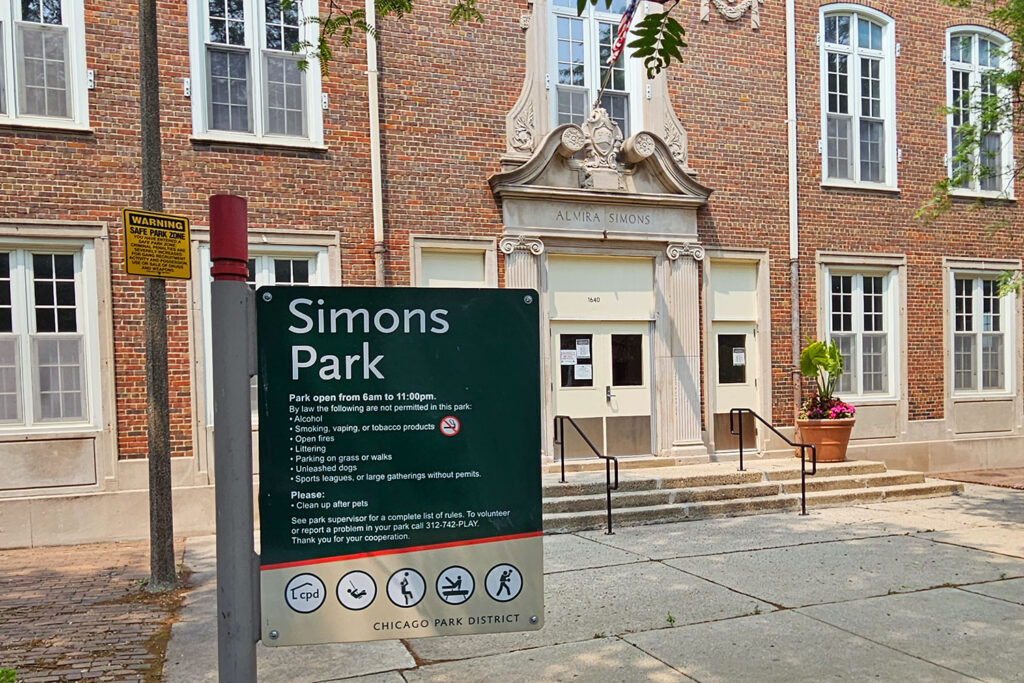

Pacific Junction lies between two other new-to-me Humboldt Park sub-neighborhoods: Simons and Garfields. I found evidence for Simons at Simons Park, 1640 N. Drake Ave., which, according to the Chicago Park District, “honors local resident Almira Simons Winkleman, daughter of early settlers Edward Simons and Laura Sprague Simons. Beginning in 1836, Edward, a northeasterner, and Laura, a former Joliet school teacher, farmed the land now bordered by Armitage, North, Central Park, and Kedzie Avenues.” However, I could find no evidence at all for Garfields. According to Mapometer, it runs along Keeler between North and Armitage. But not even a search of the Chicago Tribune historical archive yielded a reference to a Garfields neighborhood. Maybe Mapometer invented it, to fill space.

Whiskey Point, though, has a provenance, and even a modern usage. In the 1840s and ’50s, early settler George Merrill operated a tavern out of his homestead near what is now the intersection of Armitage and Grand avenues. It was a popular stop for farmers transporting produce over the plank road to Chicago. Merrill arrived decades before the Cragin brothers, who built a tin plate and sheet iron processing plant, and substituted their own name for Whiskey Point. The post office on the corner is named Cragin. Please contact U.S. Rep. Delia Ramirez and let her know that “Whiskey Point Post Office” sounds like a much more exciting place to drop off mail than a post office named after two tin-stamping brothers. Some people get it. The Whiskey Point Event Space and Garden operates near the corner. Season 10, Episode 8 of Chicago Fire is titled “What Happened at Whiskey Point?” (It may or may not be this Whiskey Point. According to Mapometer, there’s another Whiskey Point at 46th and Ashland, near Back of the Yards. Since the episode involves a warehouse fire, that sounds like a more likely location.)

Pennock is a name perhaps best forgotten. In 1881, entrepreneur and swindler Homer Pennock arrived in Chicago with a fortune amassed from a Colorado gold mine, announcing plans to build an industrial community northwest of the city limits. He attracted a refrigerator manufacturer who employed 500 men. To house the workers and their families, Pennock built dozens of dwellings along “Pennock Boulevard,” which is now Wrightwood Avenue. The train station at 4014 W. Fullerton Ave. was named Pennock. (It is now named Healy, after Lyon & Healy, a neighborhood harp manufacturer.) Pennock’s boomtown didn’t last long. The refrigerator factory burned down. Pennock left for Alaska, where he founded the town of Homer, luring settlers with “promises of gold.” The jobless workers abandoned their homes, until, according to the Tribune, “the elements, destroyers of the staunchest structures, laid hold of the buildings that the fire had spared. The brick houses began to crumble, and as Chicago began to spread toward Pennock’s abandoned village the boys made pilgrimages to the ruins and aided in the destruction. First window panes and then window casings were broken from their fastenings till soon the elements had the once proud houses at their mercy.”

However, a few Pennock houses still stand in the neighborhood now known as West Logan Square, their stucco facades painted in colorful yellows and greens. The Pennock name now exists only in the most granular detail of internet maps, but a little of the Pennock village still survives.