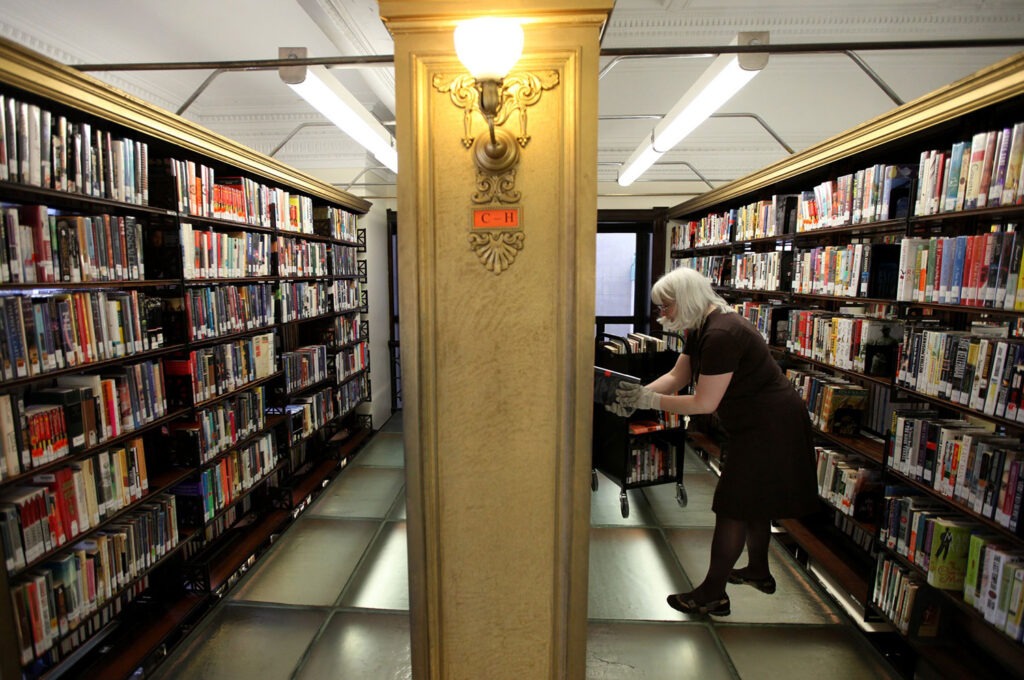

Max Grinnell, a jolly-bellied man with flowing hair and a “Chicago” shamrock t-shirt, stood in the rotunda of the Blackstone Branch of the Chicago Public Library, 4904 S. Lake Park Ave. Above his head, decorating the dome, were murals representing Art, Science, Literature and Labor. The paintings were populated by characters in classical Grecian garb. Beneath Grinnell’s feet was a tiled pattern, radiating from a red target. The bookshelves were bronzed, with a lamp at the head of each row. A pair of Ionic columns marked the entrance to the reading room.

In the entire Chicago Public Library system, there is no place like Blackstone, the city’s oldest branch, built in the gilded age year of 1904. Blackstone is the only branch that matches the classical grandeur of the original Central Library, now the Cultural Center. Every other neighborhood library fits some category of functional public architecture: the venerable Kelly, in Englewood, looks like a police station. Chicago Lawn, built in 1960, looks like a highway rest stop. Edgewater, built in a style Grinnell calls “Faux Lloyd Wright,” could be a suburban village hall.

Grinnell was about to explain why Blackstone is a classic piece of architecture and every other public library is just good enough for government work, as a docent on a Sunday afternoon tour of Blackstone and its surrounding neighborhood. An urban studies lecturer at the University of Chicago, Grinnell is the son of a librarian, which has given him a lifelong love of books and the buildings where they can be found.

“I grew up around books,” he said. “I remember my mom bringing home a pile of National Geographics. She’d bring back discarded gazetteers and atlases. We didn’t have a lot of money to travel, but I traveled through those books. Treasure Island still amazes me.”

Andrew Carnegie, the robber baron and philanthropist, built 106 libraries in Illinois in the early 20th Century. Carnegie never shared his wealth with Chicago, but we had our own library-building millionaire: Timothy Beach Blackstone, president of the Chicago and Alton Railroad. Perhaps Blackstone was motivated by competitiveness with a fellow industrialist, or by civic boosterism, but he believed a building that housed the art of literature should be a work of art in itself. Since the money came from his private fortune, rather than the public treasury, he could gild it as much as he wanted.

“Blackstone was not specifically a bookish fellow or had his own private library, but he had seen what was going on with Andrew Carnegie’s library programs, so he was very excited about creating a library for the community,” Grinnell said. “One of the things that he mentioned was he did want it to have a grand sense of presence. He wanted to get some of the people who’d been involved with the World’s Columbian Exposition, including Solon Spencer Beman, who was the architect of this building.”

Beman, who also designed the Pullman community and the Fine Art Building, modeled the library after the Erechtheion, a temple on the Acropolis in Athens. Oliver Dennett Grover, whose work had been displayed at the Columbian Exposition, painted the murals.

Blackstone, however, was not merely a pompous, insular cultural symbol. The library distributed books throughout the community. Grinnell led his dozen or so library buffs down to the corner of Lake Park and 50th, once the site of a newsstand that doubled as a lending library. Kenwood and Hyde Park are Chicago’s most bookish neighborhoods, so there was always demand.

“In the teens and the 20s, where the patrons were able to check out books in the two newsstands, they usually averaged about 1,500 to 2,000 a month. There were people picking up popular books of the time. How-to and self-help books were very popular.”

“How did people know what books were available?” someone asked.

“To the best of my understanding, people just walked by,” Grinnell said. “Essentially there was a carrell of paperbacks, and one or two shelves.”

At the Hyde Park Bank, 1525 E. 53rd St., library employees gave classes on bookkeeping and financial literacy. Nichols Park, which runs between 53rd and 55th streets, was built in the 1950s because “a group of concerned patrons of the Blackstone branch library were really intent on having more greenspace” on land cleared for urban renewal, Grinnell said as he stood in front of the Nichols Bird of Peace, the park’s famous egg-shaped sculpture. In the 1950s and ’60s, Blackstone librarians brought foreign-language volumes to students at Murray Language Academy, 5335 S. Kenwood Ave. Blackstone librarians led storytimes at the Hyde Park Neighborhood Club, 5480 S. Kenwood Ave. The Hyde Park Art Center sent artists to Blackstone to teach children painting and cartooning.

A history of Chicago’s most historic library is also, it turns out, a history of the city’s most historic neighborhoods. If you’re a library buff — and if you’ve read this far, you probably are — Grinnell is giving a talk titled “A Water Tank, Some Mighty Owls, and More: 150 Years of the Chicago Public Library” Wednesday, June 21, at 6 p.m. at the Near North Branch, 310 W. Division St. Unfortunately, Near North looks like the entrance to a sewage treatment plant. There’s only one Blackstone.