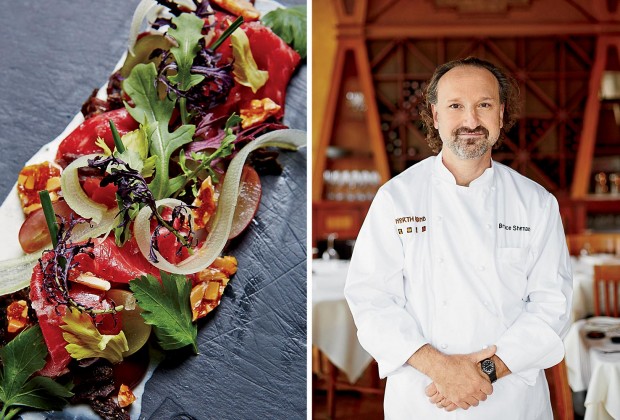

Bruce Sherman, chef-partner of North Pond since 1999, is leaving the treasured Lincoln Park spot at the end of the year. He’s not stepping down in scandal, or because real estate prices got too high, or for any of the usual reasons. Sherman is simply doing something that chefs almost never do: moving on, without a plan for the future.

“I’m ready for something new,” the 58-year-old says. “I just don’t know what that thing is.”

That something will not include the iconic Arts and Crafts lodge tucked away in the woods between Cannon and Stockton Drives. Though Sherman will remain a partner alongside Richard Mott, after New Year’s Eve, he'll turn over day-to-day kitchen operations to Tim Vidrio, the restaurant’s chef de cuisine. Like most everything else at North Pond, the changing of the guard will be quiet and dignified — no blowout dinners or victory laps — and then not much will change.

“We’ll always be focused on seasonal American cuisine,” Mott says. “We’re not going to turn into a pizza joint.”

Few chefs in Chicago are associated more deeply with their restaurants than Sherman. “How could he?” joked Mott’s wife, Gail Silver, when she learned he planned to leave. “I assumed he would be buried in the field behind the restaurant.”

To many, North Pond feels like it has always been there. But when Mott leased the onetime skaters’ shelter on a Lincoln Park fishpond from the Chicago Park District in 1998, it was falling apart. He could have easily sold hot dogs in the dilapidated brick structure; instead, he enlisted Nancy Warren, a local architect, and spent $700,000 turning the space into a bucolic retreat with wood inlay ceilings and a Fond du Lac stone chimney. (He spent another $700,000 expanding the restaurant in 2002.) The overall vibe was sedate, mature, even proudly fusty.

A year later, Sherman, a soft-spoken Chicago native who had lived and cooked in Delhi and Paris — and who'd recently left his post at the Ritz-Carlton Chicago — saw a blind ad in the Tribune and answered it. He proceeded to remake North Pond as a seasonal American restaurant years before many restaurateurs not named Alice Waters were doing so.

His vision paid off. Over the past 20 years, North Pond has been one of Chicago’s most decorated spots. In 2018, when Chicago magazine picked the 50 Best Restaurants in the city, North Pond ranked number 15. Food & Wine, James Beard, and pretty much every other food outlet hailed the place. “It is a celebratory and cozy setting that makes you want to light a fire and pop open some Champagne,” gushed Michelin, which has awarded North Pond a star for the past seven years.

They got it right. It’s no secret that I love North Pond. I have a history with the place as warm as its popping fireplace; there's something about the French doors looking out on the pond and skyline beyond that feels like the deepest déjà vu. Even on a random Wednesday, meals in the rustic space have the air of celebrations. The idea of the establishment carrying on without Sherman is hard to imagine. Then again, Vidrio, a 34-year-old Lincolnshire native, has quietly become a driving force at North Pond over the past nine years.

“Tim has been here longer than anyone except maybe the butcher, the dishwasher, and a couple of bussers,” Sherman says. “He knows how the kitchen runs. Because he has run it.”

Vidrio was predictably flattered to be handed the reins. “Bruce put his time in and built this great restaurant,” he says. “It means a lot to me that he trusts me to keep it going.”

North Pond will be fine — plans to install a new skylight in North Pond’s main dining room by next spring are still on schedule — but what happens to Bruce Sherman now? He’s spent the past 20 years succeeding largely outside of Chicago’s ever-evolving restaurant industry. His two daughters grew up while he was at North Pond. But now they’re college-aged, and times have changed.

“I leave having seen the public consciousness regarding seasonality and sustainability evolve from virtually non-existent to almost passé,” Sherman says. “And I’ll be forever grateful for, and entertained by, memories of personalities too unique to possibly believe.”

When 2020 begins, he plans to take at least four months off and enjoy a little long-awaited domestic bliss. “People keep congratulating my wife,” he says. “Now she gets to have a life and her husband back.”

After that, who knows?

“Bruce is smarter than the average bear,” Mott says. “He could do about 40 things and be a success.”