In 1993, Mayor Richard M. Daley left his bungalow on South Emerald Avenue in Bridgeport for a townhouse in Central Station, a brand-new development in the South Loop. To those who considered the Daleys inseparable from Bridgeport, it was a shocking decision — one that suggested the mayor might be losing touch with his roots.

But taken in the context of Daley's long-term vision for the South Loop — and downtown in general — the move made sense. Central Station, a billion dollar, 6,000-unit project, was built on 72 acres of land once owned by the Illinois Central Railroad.

"As the 1970s dawned, Chicago civic leaders looked both west and south of the Loop and saw decay," wrote Dennis Rodkin in Crain's Chicago Business earlier this year. "To the south were long gashes in the city grid where railroads and rail junctions lay, and to the west was skid row."

Daley was out to develop the South Loop, and who better to encourage the neighborhood's change than the gentleman in the mayor's office?

After the Daleys moved, South Loop's transformation was startling. At one time, the neighborhood's best-known institution was the Pacific Garden Mission, a homeless shelter known nationally for producing the radio program "Unshackled," which profiled inhabitants who turned their lives around by finding Jesus.

By 2004, the mission had moved out to make room for an expansion of Jones College Prep.

The key figure in the West Loop's redevelopment was Oprah Winfrey, who in 1990 began filming her talk show in a converted armory on Washington Street. Thirty years later, the site is set to become the new McDonald's headquarters, another landmark in the West Loop's transformation. Now, according to Rodkin, "virtually every trace of 20th-century decay is gone from both neighborhoods, each one now home to tens of thousands of people, as well as restaurants, high-performing public schools, parks and shopping districts."

In 1990, the census tract where Central Station is located had a median household income of $29,117 in modern dollars. By 2013, the most recent year for which American Community Survey figures are available, it was $73,286.

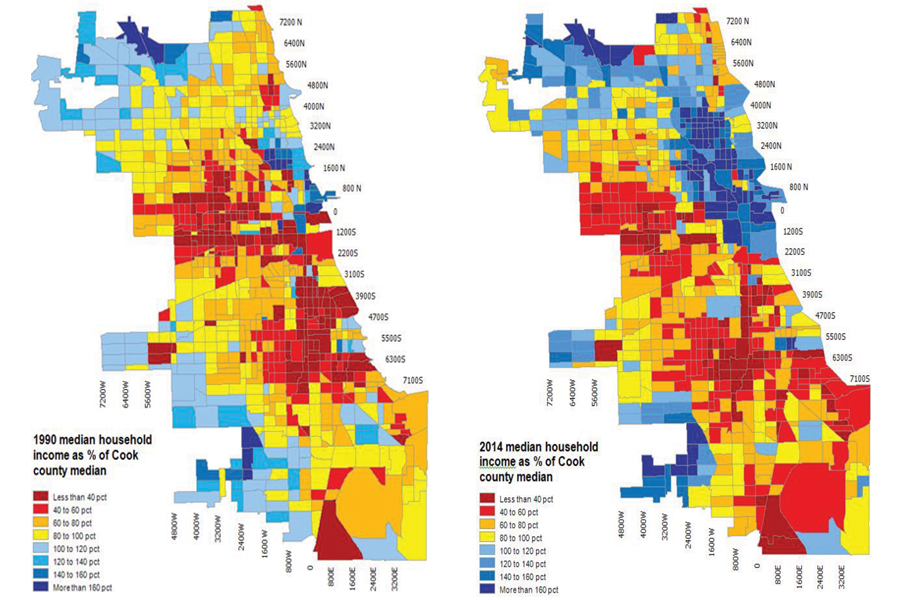

In fact, if you compare maps of average household income by census tract in 1980 and the 2010s, three areas stand out for a spike in wealth: South Loop, West Loop, and the Northwest Side, from Wicker Park and Logan Square on up to Ravenswood and Lincoln Square.

Those areas, perhaps not coincidentally, have also been the homes of our past, current, and future mayors. Daley lived in the South Loop, Rahm Emanuel lives in Ravenswood, and in 2004, Lori Lightfoot, a well-to-do lawyer, moved from Wicker Park to Logan Square.

Writing on this site last summer, Grace Perry compared Logan Square's current transformation to Lincoln Park's in the '70s:

"In the 1970s … Halsted was home to an flurry of exciting nightlife, including the iconic gay/punk hang La Mere Vipere. That burgeoning alternative scene lived alongside a robust working-class Latino community, who settled in Lincoln Park after immigrating from Puerto Rico in the ’50s and ’60s. Through the ’80s, urbanities moved in for cheap rent. Eventually, young families bought houses, forcing area residents west into Logan Square and Humboldt Park … Logan is a boho paradise no more. Not only are its longtime residents gone, those first-wave gentrifiers have also been chased out by rising rents. In their absence, the area has transformed into the type of yuppie haven it served as a reprieve from."

On these census maps, it's startling to see the Northwest Side's change from orange and red to solid dark blue, a color representing tracts where residents earn more than 160 percent of Cook County's median income.

In the census tract encompassing Milwaukee and Fullerton — home to the Whistler, Gaslight Coffee, and Lightfoot's favorite bar, Emporium — income jumped from $48,692 to $71,214. In Mayor Emanuel's neighborhood, it went from $51,306 to $74,612.

It makes sense that you'd find a mayor in a gentrifying neighborhood. Mayors are members of the elite professional class, whose arrival represents the final stage of gentrification.

Also, the mayors we elect reflect who we are — and what we're becoming as a city. Over the past 30 years, Chicago's well-to-do have flocked to neighborhoods close to the urban core — the same areas their parents once abandoned for the suburbs. That's quite literally Emanuel's story. His parents moved from Uptown to Wilmette; when Rahm was old enough, he moved back into the city.

Like it or not, gentrification has shaped Chicago into what it is today. We may claim to hate the game, but we keep electing the players.