Illinois’s official slogan is “Land of Lincoln.” It’s an irony of history that the state with the worst politicians in America also produced one of the best. Lincoln went off to Washington, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and won the Civil War, all with such disregard for his own personal gain that he became known as “Honest Abe.”

That doesn’t sound like an Illinois politician, and Lincoln was never much of a success in his home state. He served a few terms in the legislature and a single term in Congress, but he was defeated in two bids for the U.S. Senate, unable to bribe or manipulate enough legislators into backing his candidacy.

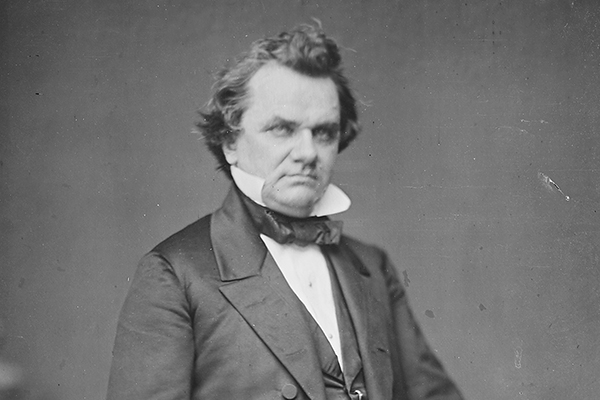

The man who really established our state’s shady political culture was Lincoln’s nemesis, Stephen A. Douglas, who vanquished Lincoln in his second losing Senate campaign. Douglas was ambitious, backstabbing, avaricious, and more practical than principled. He never hesitated to trade jobs or votes for political or pecuniary advantage. We really should call our state the Land of Douglas, not the Land of Lincoln.

As soon as Douglas arrived in Illinois from Vermont, he raced up the state’s political ladder. According to The Long Pursuit: Abraham Lincoln’s Thirty-Year Struggle with Stephen Douglas for the Heart and Soul of America, the 21-year-old Douglas made his debut in Illinois politics as “a one-man lobbying effort — mainly for himself.” Douglas, a Democrat, wanted to snatch the office of Morgan County state’s attorney from a political rival, but that office was appointed by the governor, who was a Whig. Douglas’s solution? He worked to change the law so that state’s attorneys were elected by the legislature, which was controlled by his party. He succeeded, both in rewriting the statute, and winning the state’s attorney post.

After maneuvering his way into that first office, Douglas double dipped by getting himself elected state representative. Then he tripled dipped by accepting a presidential appointment as registrar of the Springfield Land Office. After that, Douglas served as secretary of state, state supreme court justice, and congressman, until he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1847, at the age of 33. Douglas used that position to dominate the Illinois Democratic Party, which ruled the state before the Civil War. Through his influence over federal patronage, Douglas built a political machine, placing his loyalists in positions which then enabled them to exercise clout over local politics. More than a century before Richard J. Daley brought the Chicago Machine to its apotheosis, through his distribution of jobs and his tight control of slating for statewide offices, Douglas was the state’s first political boss.

“He controlled every Federal office in Illinois, and through his friends he practically controlled almost every state and county office,” wrote Henry Parker Willis in his biography of Douglas.

Douglas’s best-known legislative move was the Kansas-Nebraska Act. By allowing settlers in those two territories to vote on whether to allow slavery, it blew up the Missouri Compromise, which used latitude to divide slave and free territory. That, in turn, revived the political career of Abraham Lincoln, and helped bring about the Civil War.

Douglas’s motive had less to do with expanding slavery than it did with… benefiting Stephen Douglas. (He explicitly didn’t want slavery in Illinois.)

His real goal was to build a transcontinental railroad that would pass through his hometown of Chicago, then follow a northern route toward the Pacific. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was Douglas’s method of winning Southern senators’ support for that scheme, as it would allow Southerners to bring slaves into the new territories the railroad would create.

Not only would that railroad establish Chicago as the nation’s transportation hub. It was mapped to run across land that Douglas and his political allies owned in the city. Anticipating that a spur of the railroad would terminate at what is now Superior, Wisconsin, Douglas invested in 6,000 acres there. The land quickly became worth $20,000 a lot.

History remembers Douglas mainly as the foil to a future president in the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. At the time, though, Lincoln played second banana to Douglas, one of the most celebrated politicians of the 1850s. Douglas was the reason the Illinois Senate campaign received nationwide newspaper coverage — coverage that made Lincoln a national figure, and a contender for the 1860 Republican presidential nomination. As one historian succinctly put it, “No Douglas, no Lincoln.”

During the Great Secession Winter that followed Lincoln’s election, Douglas worked in the Senate to craft a compromise that would hold the country together against what he saw as the extremes of Northern abolitionism and Southern disunionism. After his efforts failed, he pledged his support to the Union, and collaborated on the war effort with his old rival Lincoln.

The Civil War broke him, though. He returned home to Oakenwald, his estate on the shores of Lake Michigan, where he died on June 3, 1861, at the age of 48, less than two months after Fort Sumter. He's buried at the end of 35th Street, beneath a 70-foot-tall monument, in the neighborhood that bears his name.

Douglas deserves a bigger role in the history of Illinois politics. We should remember him every time an Illinois politician collects salaries for two (or three) offices, every time an Illinois politician writes a law that benefits himself financially or politically, every time an Illinois politician appoints a friend or an ally to a well-paying government job. Whenever our politicians get into some hinky business, they’re just following the lead of the Little Giant.