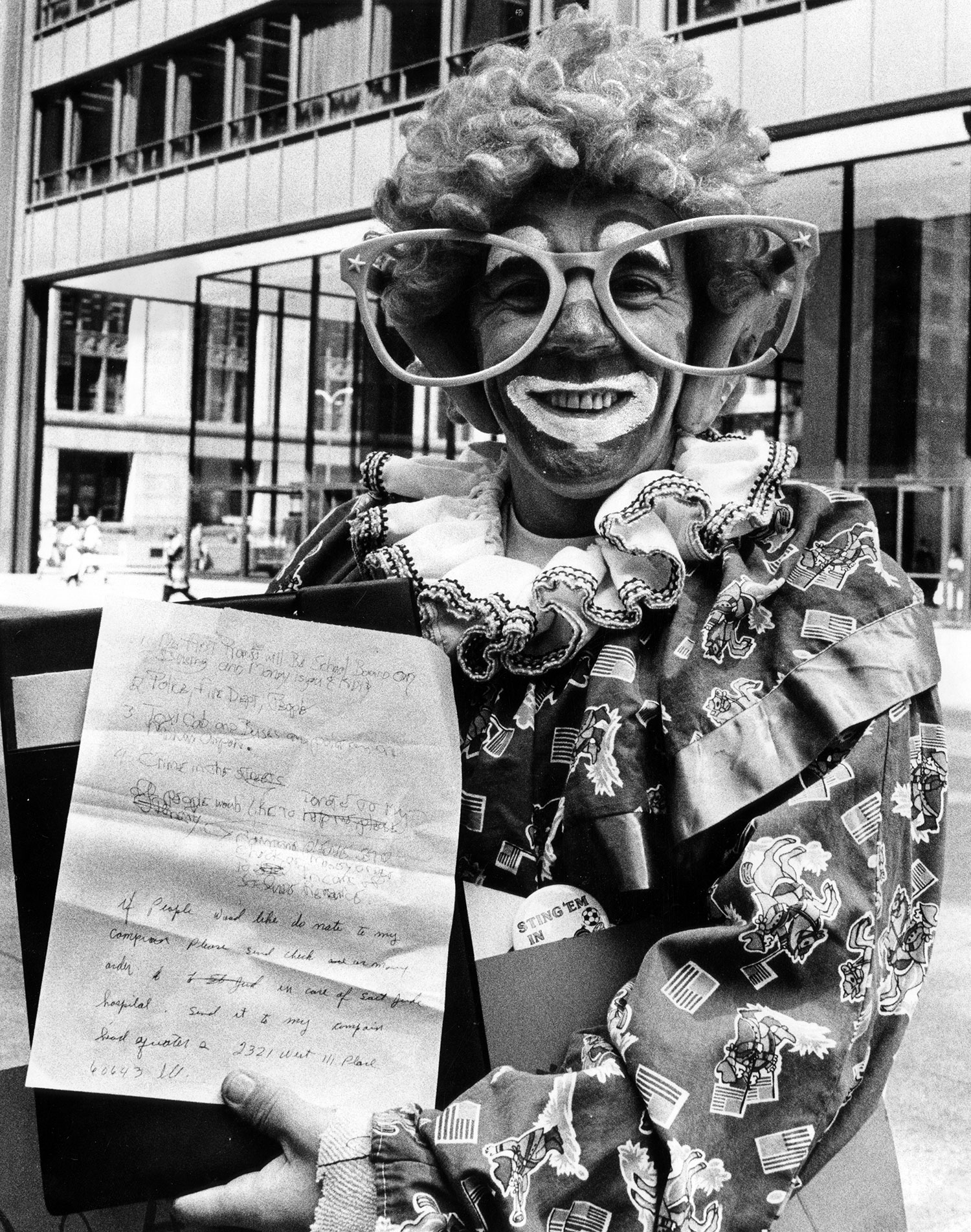

The last Republican candidate for mayor of Chicago was, literally, a clown.

His name was Ray Wardingley. He had once performed as “Spanky the Clown” to raise money for the cancer ward at St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital. Wardingley had also filled in as Stanley Sting, the mascot of the Chicago Sting soccer club. At five-foot-four, he fit the costume.

By 1995, the 60-year-old Wardingley had retired from entertainment, and was piecing together a living in Morgan Park, dispatching cabs, sweeping up at a barbershop. He won the Republican primary with 2,438 votes, probably because his name was at the top of the ballot, then got 2.8 percent of the vote in the general election against Democrat Richard M. Daley and Independent Roland Burris.

“I don’t think I’ll get publicity, television or radio,” Wardingley told the Reader during the campaign. “I’m not spending any money on television. They don’t feel any Republican can win anyway. They don’t even want me on the ballot. Imagine a guy, a clown, winning, being the candidate for the Republican Party?”

The Republicans certainly didn’t want Wardingley on the ballot; they found an ex-clown so embarrassing, so damaging to their brand, that they decided to do away with Republican primaries for mayor altogether. Democratic primaries, too.

The year before, Republicans had won the state House, temporarily kicking Michael Madigan out of the speaker’s chair. With total control over Springfield, they passed a bill making Chicago elections nonpartisan, establishing the runoff system we use today. A prominent Republican, such as then-state’s attorney Jack O’Malley, might have a chance to win the mayor’s office if he didn’t have to run with an “R” beside his name.

Black politicians saw the bill as a racist plot to lock them out of the mayor’s office. Washington won the 1983 Democratic primary with 36 percent of the vote, against Daley and incumbent Jane Byrne, who divided the white vote. In 1986, to prevent a repeat of that primary, white ethnic politicians attempted to pass a referendum establishing nonpartisan elections. Washington crowded it off the ballot with three meaningless advisory measures.

“We think we can make a case in federal court that white Democrats and white Republicans have come together with a scheme to prevent African-Americans of the Harold Washington from becoming mayor,” said a spokesman for the Harold Washington Party, which was formed after the mayor’s death to elect another Black mayor, and would no longer be able to run its own candidates if the bill passed. “We clearly see it as a voting rights violation.”

County Clerk David Orr, who briefly served as mayor after Washington’s death, would call nonpartisan mayoral elections a “blatant racist attempt to hurt the Black vote.”

That’s how the runoff system looked in 1995. Chicago was only a dozen years removed from a mayoral election in which Washington received 99 percent of the vote in Black wards, while his white Republican opponent, Bernard Epton, ran up margins almost as big in white wards.

In the 2020s, though, a nonpartisan election is doing the opposite of what the Harold Washington Party screamed about. It did indeed prevent Chicago from electing a mayor who appealed only to his own race, but it was a white mayor, not a Black mayor — exactly the kind of mayor those scheming white ethnic politicians hoped to replace Harold Washington with: a moderate Greek-American popular with the cops and firefighters in their wards.

As the only white candidate against seven Black candidates, Vallas finished first in February. He would have won a first-past-the-post Democratic primary. In a city that is 36 percent white, though, he could not build a majority.

Appeals to racial solidarity don’t work like they used to. Chicago has now elected two consecutive Black mayors, but neither ran as champions of their race. In 2019, Lori Lightfoot was the champion of white reformers on the lakefront. In 2023, Brandon Johnson was the champion of white progressives along Milwaukee Avenue.

“He’s a cool young Justin Trudeau of the Chicago mayor’s race,” pollster Matt Podgorski said of Johnson. “He’s not running as a Black dude. He’s just running as a young kind of hip teacher.”

In February, Johnson finished third in most Black wards, behind Willie Wilson and Lori Lightfoot, who tried to reinvent herself as the Black candidate, and got the defeat she deserved. Johnson won 80 percent of the Black vote in the runoff, but that’s far from the unanimous support Harold Washington received in his community.

The Republicans who gave us nonpartisan elections did not do so with the city’s best interests in mind. They did so with their party’s best interests in mind. That’s what politicians do. (If you believe Johnson’s claim that Vallas is a Republican, it turned out to be a self-own.) While nonpartisan elections may have been intended to restore or solidify white rule in City Hall, they have helped Chicago move past the racial divisions of the era in which they were first proposed.

Thanks, Spanky.