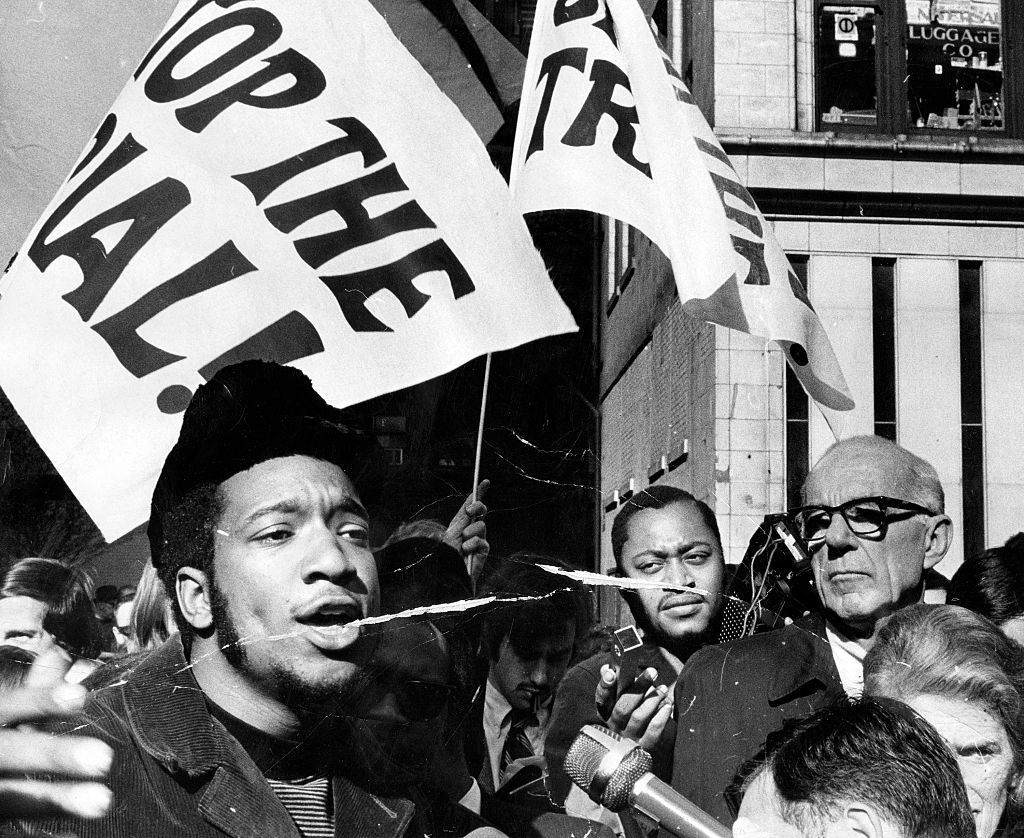

Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, died at the age of 21. It was a short life, but it changed Chicago politics — and America — forever.

Hampton, played by Daniel Kaluuya in the the new movie Judas and the Black Messiah (released last week in theaters and on HBO) was shot to death on December 4, 1969, in a raid carried out by officers of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, working with intelligence provided by an FBI informant.

Throughout the 1960s, Chicago’s Black politicians were known as a dependable cog in Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Machine, so much so that a group of Black aldermen were nicknamed the “Silent Six” for quietly voting with the mayor.

After Hampton was killed, that all changed. State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan, an Irishman considered next in line for the mayor’s office, was up for re-election in 1972. That year, for the first time, Black voters stood up to the Machine. They pasted “CONVICT” over “RE-ELECT” on Hanrahan billboards, and voted instead for Republican Bernard Carey, who was elected with support from the inner city and the suburbs.

That state’s attorney’s election was the birth of independent Black politics in Chicago. Before his death, Hampton had created the template its success: a “Rainbow Coalition” of Black, Latino, and poor white voters. In one Judas scene, Hampton addresses a rally alongside Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez, the leader of the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican gang that resisted gentrification and urban renewal in Lincoln Park.

“Chicago’s the most segregated city in America,” Hampton says. “Not Shreveport. Not Birmingham. We’re here to change that: The Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and the Young Patriots” — a group of poor white Appalachians from Uptown — “are forming a Rainbow Coalition of oppressed brothers and sisters of every color.”

The Rainbow Coalition, of course, was the name Jesse Jackson gave to the movement that supported his 1984 presidential campaign. But more locally, and more successfully, it was the constituency that elected Harold Washington mayor in 1983. In fact, in his book From the Bullet to the Ballot, Indiana University history professor Jakobi Williams argues that Hampton’s coalition led to the election of both Washington and the presidency of Barack Obama:

“This group and its popularization of the concept of class solidarity changed the political landscape of Chicago by helping to severely weaken the city’s Democratic machine,” writes Williams, who grew up in Englewood. Hampton’s killing “helped unite African American, Latino, and progressive white groups and activists in a political movement against the Daley machine.”

Those, of course, were the groups that elected Washington. When Obama moved to Chicago to work as a community organizer in 1985, Washington was a big part of his attraction to the city. (While still living in New York, Obama had tried to land a job with the Washington’s administration.)

As a young Obama tried to organize laid-off white steelworkers and Black CHA dwellers, writes Williams, “there was a model for Obama to follow in trying to determine how to put together a successful racial coalition in Chicago: that of recently elected mayor Harold Washington, whose coalition building linked to the original Rainbow Coalition.”

Ironically, the only bump in Obama’s road to the White House was his defeat in a 2000 congressional primary by Rep. Bobby Rush, the Illinois Black Panther Party’s Minister of Defense. Rush and his Black nationalist allies portrayed Obama as an elitist, an outsider to the community, and a tool of the University of Chicago: “the white man in blackface,” as the third candidate in that race, Donne Trotter, once told me.

(Rush, for his part, has endorsed Judas as a film that “must be seen by all freedom-seeking, justice-seeking, good-hearted Americans.” His character, played by Darrell Britt-Gibson, is a constant presence alongside Hampton in the movie, though he doesn’t have many lines. Hampton was the dynamic spokesman, Rush the silent survivor.)

Obama was lucky to lose that race to Rush. Obama, not Hampton’s fellow Black Panther, was the true avatar of Rainbow Coalition politics. Running to represent a Black majority congressional district, Obama failed dismally. Four years later, he succeeded brilliantly at building a coalition of Black and white progressives, which elected him to the Senate, and then the presidency.

Obama had the help of David Axelrod, who covered Harold Washington’s election as a political correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. Writes Williams, “Axelrod wasted little time parallelling Obama’s Senate bid in 2004 with Harold Washington’s 1983 mayoral election to maintain the support of the racial coalition that was crucial to the election of Chicago’s first African American mayor.”

According to Judas and the Black Messiah, Black power was what FBI director J. Edgar Hoover feared when he engineered Hampton’s assassination. They may have killed the man, but they couldn’t kill his movement.

Comments are closed.