You wake up at seven, drag your phone off the nightstand, open Twitter, and see this message from @cta: "Buses and trains are not in service due to a transit workers strike. We encourage you to find alternate means of transportation, and hope to resolve this situation as quickly as possible."

You rented your apartment because it's near an 'L' stop. Door to door to your job in the Loop is 45 minutes. But the 'L' isn't running today, and you have to be at work by nine. You turn on WGN, which is broadcasting the transpocalypse: a helicopter shot of the Kennedy, jammed from Montrose to Grand with cars moving five miles an hour. On Google Maps, every street is red.

Stepping out onto the sidewalk, you try to hail an Uber. Every driver in Chicago is working this morning, but getting downtown will take 90 minutes and cost $50, twice as much as an ordinary day. You head to a Divvy station, but all the docks are empty. You don't own a car or bicycle — living near the 'L' and Divvy, why would you? So you set off for work on foot, alongside more pedestrians than you've ever seen at this time of day in your neighborhood.

Last Friday, Paris experienced a one-day transit strike. Rail and bus workers walked off the job in protest of President Emmanuel Macron's plan to overhaul France's pension system. According to one newspaper, "[officials] counted more than 380km of traffic jams … during the peak of the evening rush hour — more than double the usual amount." Parisians got around on bikes and scooters, and "[r]ide-hailing services appeared to profit from surge pricing due to high demand, with some reporting fares three times higher than normal."

Public employees striking over pensions certainly sounds like something that could happen in Chicago, even though the CTA says it's illegal under transit workers' collective bargaining agreement. It happened in 2005 in New York City, and twice in 2013 in the Bay Area.

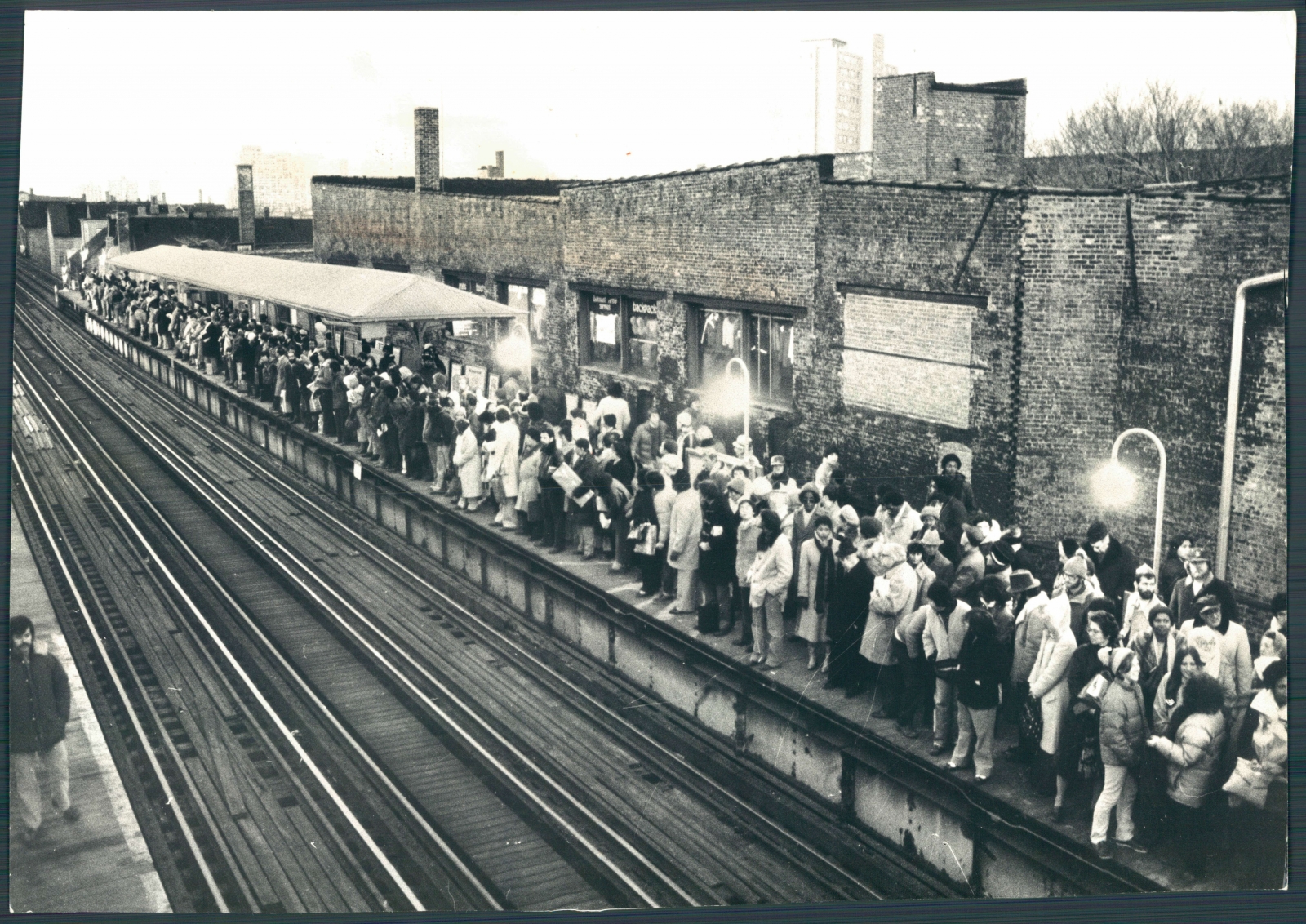

The last time Chicago saw a shutdown was in 1979. The CTA was closed for three days just before Christmas as the Amalgamated Transit Union demanded a higher cost-of-living adjustment from newly elected Mayor Jane Byrne. Wrote the Washington Post:

"The walkout snarled downtown streets and expressways as CTA riders sought ways of getting to work. As the morning rush hour continued into midday, some who drove to work reported their trips had taken five times longer than usual … In response to the strike, the mayor lifted normal parking restrictions in the Loop and asked citizens to help each other get to work … Absenteeism was believed to be high and downtown offices, and many retailers reported a decline in business during the usually hectic week before Christmas."

A contemporary transit shutdown would still be a huge pain, but it might not be as bad as it was 40 years ago. Today, commuters have a longer menu of transportation options, to say nothing of cell phones and the internet, which allow us to summon rides to work and, for some, work from home.

As for the pain part: there are 1.6 million rides a day on the CTA. Assuming those are all roundtrip, that's 800,000 people who'd need to find a new way to get where they're going.

Also, Chicago already has some of the worst commuter traffic in the country. According to a 2013 Census Bureau study, 139,477 cars drive into Cook County each day from DuPage County, on top of 93,471 from Will and 80,833 from Lake. Those numbers may be even higher now, as corporations continue to move their headquarters from the suburbs to the city. And that doesn't even count trips within Cook County. Imagine if all those drivers were suddenly joined by commuters who could no longer ride the Metra, which averages 288,100 trips every weekday.

I asked John Greenfield, editor of the transportation website Streetsblog Chicago, to forecast the consequences of a transit strike. He wrote, via email:

"[I]f CTA, Metra, and South Shore Line (and river taxi?) service just ceased to exist due to an across-the-board strike, what would happen? There would probably be a lot more driving of personal cars, especially from the suburbs, which of course would of course result in horrible traffic jams, dangerous air quality alerts, an increase in crashes, difficulty for first responders to get to emergencies, etc. It would be a major problem."

The city is currently in the process of introducing electrical-assist Divvy bicycles. That would make a commute downtown easier for those who could score a bike. A scooter would, too, but those are currently limited to the West and Northwest sides. Maybe, as was the case in Paris, Divvy and scooters would be free during the strike. If the city can't get its act together with the unions, it ought to at least help us get around.

In a Chicago transit strike, AirBnB hosts with beds near the Loop would also stand to make a killing. During a 13-day New York City transit strike in 1980, some commuters rented hotel rooms in Manhattan.

Joseph Schwieterman, the director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul, called the prospect of a Metra, CTA, and Pace strike "frightful."

However, he added, "If any one of these entities struck, the effects would be a lot less severe than even a decade or so ago. App-based services like Lyft, Uber, and SpotHero give people new options. Plus, some people making short hop trips would have access not only to Divvy but an increased number of private bicycles. Perhaps the biggest change for many is the ability to work from home or head to your nearest Starbucks."

Precisely because there are more options, "labor unions likely recognize that there are much greater risks of permanent job losses as a result of a service disruption than years ago" — which could make a strike less likely. "Some routes, particularly lightly used bus lines, are already on the bubble due to recent ridership losses."

According to the Census Bureau, 27.5 percent of the households in Chicago do not own a personal vehicle. That's one of the highest rates in the nation, and it's increasing. We're more likely than other cities to suffer in public transportation freeze, but it's also less important for us to work in one place than it used to be. (That option, of course, is mostly limited to white-collar jobs, but Chicago has been gaining white-collar jobs while losing blue-collar jobs for years.)

Still, best to hope we never wake up to that tweet.