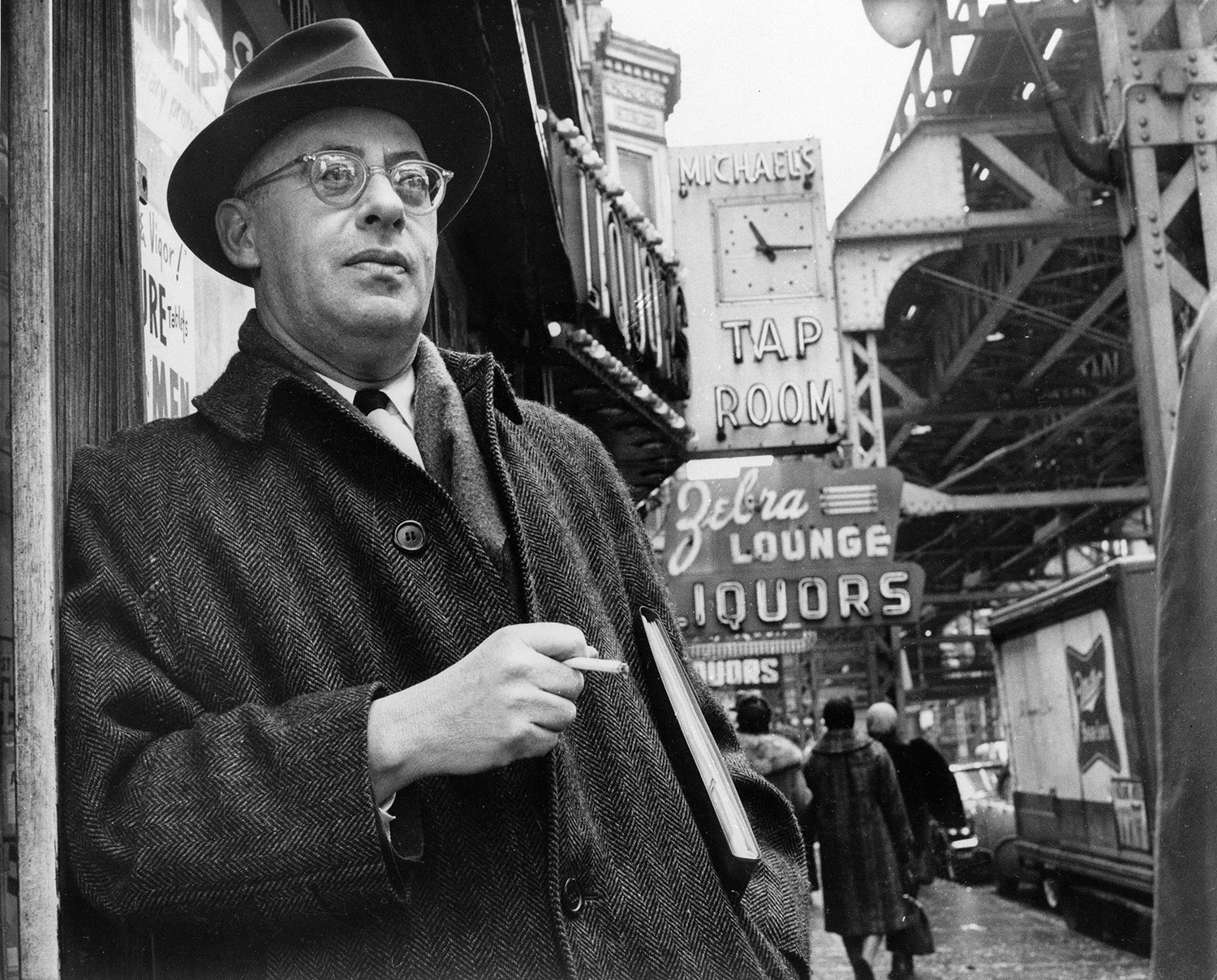

In 1966, Saul Alinsky, that South Side troublemaker, decided to take on Richard J. Daley’s Machine. Alinsky, founder of The Woodlawn Organization and father of community organizing, hatched a plan to defeat two Machine-backed congressmen on the South Side. If he succeeded, wrote Sanford J. Horwitt in Let Them Call Me Rebel, his biography of Alinsky, “the political map of Chicago would be forever changed. Not only would blacks have a claim on an unprecedented amount of power in Chicago but Daley’s role as a kingmaker in national politics would be vastly diminished.”

Alinsky did not succeed. The old hacks won, with Daley’s support. Daley never forgave anyone who challenged his power. After Alinsky died, in 1972, a goo-goo alderman offered a motion to name a park after him. Daley sent it to a committee “where other noble ideas were also buried.”

Saul Alinsky could not beat the Machine in its heyday, but the heirs to his movement have finished the job he started more than half a century ago. Today, the last Machine politicians from Mayor Daley’s day are out of office and facing federal corruption trials, and a labor organizer is mayor. The Machine defined Chicago politics in the 20th Century. Organizing, as pioneered by Alinsky, defines it in the 21st.

This change began, of course, with Barack Obama, who moved to Chicago in 1985 to work as an organizer with the Developing Communities Project on the Far South Side. When residents of Altgeld Gardens wanted the Chicago Housing Authority to remove asbestos from their apartments, Obama bused them down to CHA headquarters to demand a meeting with the director. Alinsky had done the same thing to Daley in the 1960s, busing a caravan of blue-collar South Siders to City Hall to force a compromise on the University of Chicago’s plan to redevelop its surrounding neighborhoods.

“No one can negotiate without the power to compel negotiation,” Alinsky wrote in Rules for Radicals, his manual for sticking it to The Man. “This is the function of the community organizer. Anything otherwise is wishful non-thinking. To attempt to operate on a good-will rather than on a power basis would be to attempt something that has not yet been experienced.”

Obama was conscious enough of Alinsky’s influence to write a chapter titled “Why Organize? Promise and Problems in the Inner City,” for the anthology After Alinsky: Community Organizing in Illinois. But Obama left organizing to attend Harvard Law School. He was tired of being on the outside, begging politicians for money. He wanted to be on the inside, handing it out himself. Obama collaborated with Machine politicians during his rise to the presidency: as a state senator, he was a protégé of Senate President Emil Jones. He ran for U.S. Senate with the support of Mayor Richard M. Daley (who may have wanted to send a potential challenger to Washington). John McCain tried to convince voters that Obama was “born of the corrupt Chicago political machine,” but the accusation didn’t stick. Obama worked with the Machine, but, being from Hyde Park, and before that, Honolulu, he was not of the Machine.

Brandon Johnson has never called Alinsky an influence. He doesn’t have to, any more than a physicist has to declare his debt to Isaac Newton. In 2015, as an organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union, Johnson took part in a hunger strike to prevent the Chicago Board of Education from closing Walter H. Dyett High School. Alinsky himself never oversaw a hunger strike, but it fit with his modus operandi: the powerless using their moral authority to embarrass the powerful.

Cook County Democratic Party chairwoman Toni Preckwinkle was Johnson’s mentor during his time on the County Board, but he didn’t need the help of any Machine politicians to become mayor. He was part of his own machine: the Chicago Teachers Union, which had been trying to elect its own candidate for mayor since Rahm Emanuel closed 50 schools. Johnson, who remained on the union’s payroll even as he served on the County Board, approached CTU leadership about running. His candidacy was approved by the union’s House of Delegates — the equivalent of being slated by the Democratic Party’s central committee. The CTU’s political arm, United Working Families, has a door-knocking crew that rivals any ward committeeman’s patronage army in numbers and enthusiasm. Those volunteers helped Johnson defeat an opponent who outspent him, 2-1. That fit in with Old Man Daley’s defense of the Machine as a vehicle for defeating money with foot soldiers: “The rich guys can get elected on their money, but somebody like me, an ordinary person, needs the party.”

“The Chicago model is rooted in the labor movement,” says Jacobin magazine editor Micah Uetricht, author of Strike for America: Chicago Teachers Against Austerity, a book about the 2012 CTU strike. Alinsky started off organizing meat packers, then went on to work with the urban poor. “It believes in democracy and militancy in the labor movement, and has adopted a broad agenda on behalf of the working class.”

According to Uetricht, Johnson is the first “rank-and-file activist from a union elevated because of strikes and other organizing to the mayoralty of a major American city.”

Chicago was once renowned for Machine politics; it should now be just as renowned for labor and community organizers’ capture of the political process. Saul Alinsky has finally beaten the Machine.