The fastest shrinking county in the United States is at the southern tip of Illinois, where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi. Alexander County lost 20 percent of its population between 2010 and 2020, falling from 7,821 people to 6,260.

Alexander’s county seat is Cairo. Once a bustling river port and a strategic outpost during the Civil War, Cairo’s population has declined from 15,000 in the mid-20th Century to around 2,000 today, as the barges stopped calling and the railroads and I-57 bypassed the town. Cairo’s only chain restaurant, a Subway, closed several years ago. In 2017, the Department of Housing and Urban Development shut down two apartment houses there, dispersing their residents throughout Little Egypt. Then-HUD secretary Ben Carson called Cairo “a dying community.”

“There is no grocery store,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote at the time. “No hospital. No community center, so the high school gym hosts weddings and post-funeral meals and pickup basketball.”

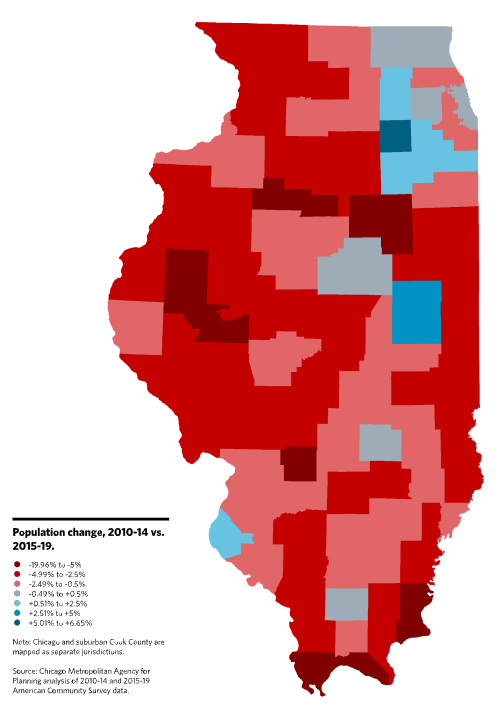

Illinois lost more people than any state in the 2010s: 243,102, according to a new report by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning based on Census estimates released in December. By percentage, we were second only to West Virginia in population loss (1.89 to their 3.68).

To see where Illinois is shrinking, look Downstate. Outside of the Chicago area, only five counties gained population: McLean, Champaign, Effingham, Williamson, and Monroe. Most of those contain, or are near, universities. The exception, Effingham, is a transportation hub, at the intersection of I-57 and I-70.

The Chicago area mostly held steady in population. The city lost only 3,000 people during the decade, while Cook County lost 29,552, a .57 percent decline.

However, in most states, rural population loss has been offset by urban growth. Chicago’s growth rate is 46th out of 50 in the nation, leading only the Rust Belt cities of Buffalo, Cleveland, Hartford, and Pittsburgh. So we’re also responsible for Illinois’s decline.

“Our situation is typical of rural America,” says John Jackson of Southern Illinois University’s Paul Simon Public Policy Institute. “Towns that used to be market towns are now drying up, disappearing. The possibilities of keeping young people there are difficult.”

Coal and manufacturing, once the basis of the region’s economy, are now negligible factors in employment. There are fewer than 3,000 miners left in Illinois, down from an all-time high of 50,000.

“Coal is a cultural factor, still a major part of the political culture,” Jackson says. “As an economic factor, it’s almost totally disappeared. Industrial isn’t coming back. All these little towns have an industrial park. That’s not working. Executives don’t want to live in areas that are deserts for people who make those decisions.”

For that exact reason, Caterpillar and ADM moved their headquarters to the Chicago area from Peoria and Decatur respectively.

Chicago’s economic dominance of Illinois is one of the factors holding Downstate back, says University of Illinois sociology professor Cynthia Buckley. Jobs and talent are migrating from the small towns to the big city, preventing Downstate from developing a 21st Century economy.

“We have one huge city, and then a lot of micro-urban areas, and a lot of very sparsely populated areas,” Buckley says. “A kid doesn’t want to study hard, get a good education, and move to Tolono. There isn’t that sort of Downstate diversification, investment in green energy and IT. Much of that would get sucked up into Chicagoland.”

Loss of population means loss of power. Illinois is guaranteed to lose a congressional seat, dropping the size of our delegation from 18 to 17. That’s the lowest number since the Civil War era, when Illinois was one of the fastest-growing states. The legislature will probably eliminate the seat of freshman Rep. Mary Miller, who represents southeastern Illinois, from Danville to Metropolis.

However, if the state invests in high-speed Internet, roads, and colleges, the 2030 Census could look a lot different, according to both professors. Since the 1960s, economic changes have been detrimental to the region. But the shifts resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic could benefit Downstate, if remote workers migrate from cities to less expensive rural areas.

“Remote work has demonstrated there are things you can do if you have high-speed Internet,” Jackson says. “Some of these semi-urban small cities are viable places for young people to live, and not just old people.”

After every Census, we read about Downstate’s decline. Ten years from now, we may be reading about its revival.

Comments are closed.