Last week, the Tribune’s architecture critic, Blair Kamin, stepped down after 28 years in the role, preceded by a stint as a news reporter for the paper, two books, and a Pulitzer Prize.

Kamin’s beat is one that evolves slowly, because building things takes a long time, and the ramifications of our built environment take even more time to become apparent. So Chicago has been lucky to have Kamin in his job for this long (as well as his predecessor, Pulitzer-winner Paul Gapp, the newspaper’s first architecture critic, who was there for 18 years). For nearly three decades, Kamin has been able to absorb and influence the changes to our buildings, parks, transportation, and policy. That’s important in every city — but especially in Chicago.

I spoke with Kamin about his time covering our built environment.

How did you go from architecture school to reporting to architecture criticism?

Well, it’s really the reverse. I went from reporting to architecture school, and then the criticism. I grew up in a newspaper family in New Jersey. My father edited a small suburban newspaper on the Jersey Shore. And so I was serving coffee on election nights when I was a teenager. Then I had an internship at my father’s paper.

The architecture part of the story started when I was in college, at Amherst, and I took a class in Gothic architecture, and that really awakened my interest in the field. After that, I went to graduate school for architecture at Yale, and then worked at the Des Moines Register mostly as a reporter, but occasionally as an architecture critic, before coming to Chicago.

Did you think at any point you might want to be an architect?

Yeah, actually. After college, I had this internal debate as to whether I should try to write about architectural practices. So after college, I went out to San Francisco and worked for two design firms. My first job in architecture was as an office clerk for an interior design and architectural firm. One of my jobs was to run the blueprint machine, which emitted these noxious fumes that made my nose wrinkle. I also worked for another architectural firm doing PR, and ultimately, I decided that I would be better off writing about architecture than practicing it.

And the wisdom of that choice was confirmed. Early on at Yale, I was taking part in an urban design class and our assignment was to go out and draw a public space in New Haven. I pinned up my drawing and one of the architecture students looked at it and said, Oh, that looks like naive art. That insult really did confirm the wisdom of my decision to be a critic rather than a practitioner.

One of your first big series was about public housing in Chicago — the legacy of the high rise buildings and the need to diversify public housing going forward so it works in different contexts. Do you do you think that’s happened? I’m curious about your reflections on public housing in Chicago since then.

So you’re referring to a 1995 series, called Shelter by Design. It explored best practices in low-income housing. [It was] an attempt to raise expectations for that type of housing and provide alternatives to was then the current [Chicago Housing Authority] high rise situation, which obviously was not good.

In retrospect, I’m glad that many of the concepts that were discussed in that series form the CHA’s Plan for Transformation. For example, New Urbanism, or defensible space, or the need for mixed income housing that tried to break down the concentrations of poverty that the high-rises had become.

Also since then, I’ve been glad to see new concepts emerge like the co-located projects, which combine public housing and public libraries, that Rahm Emanuel championed, and architects like John Rona executed so, so beautifully.

Overall, though, I would say that the Plan for Transformation has been a disappointment. It took far too long. It built too little housing. The overall aim of integrating very poor people into their communities and the city at large has not been fully achieved. The continued segregation of Chicago by race and class continues. I guess you could say that the series helped set the agenda or some of the reforms that occurred, but I’m surely not satisfied with the outcome.

For low-income housing to succeed, it doesn’t need to be an architectural showplace. It just needs to do the basics, right. It needs to provide shelter, it needs to provide community, it needs to provide integration into the broader society, so [that] people can climb the ladder, economically and socially, if they want to. It doesn’t need to win a design award, although good design certainly can be a part of its success.

I do think it’s really important to say that design is not deterministic. In other words words, better buildings will not make better people. Design is part of the equation of integrating the very poor into the city. But it can’t do it all by itself. It’s naive to think that. It needs to be combined with social service programs, and other things — schools, families that are supportive — in order for it to succeed. Design can open the door to success, but it cannot achieve that on its own.

And the corollary is true, too. You can’t blame bad design for the failures completely. You can’t completely blame bad design for the failures of high-rise public housing. The failure has had to do as much with federal policy that was well intentioned, but foolish. Concentrating lots of very poor people and a vast high rise development, like the Robert Taylor Homes or Stateway Gardens, was an invitation to disaster. In a way, it didn’t matter how the buildings were designed. The design simply accentuated the social problem of these high concentrations of poverty.

Can you explain how the design exacerbated that?

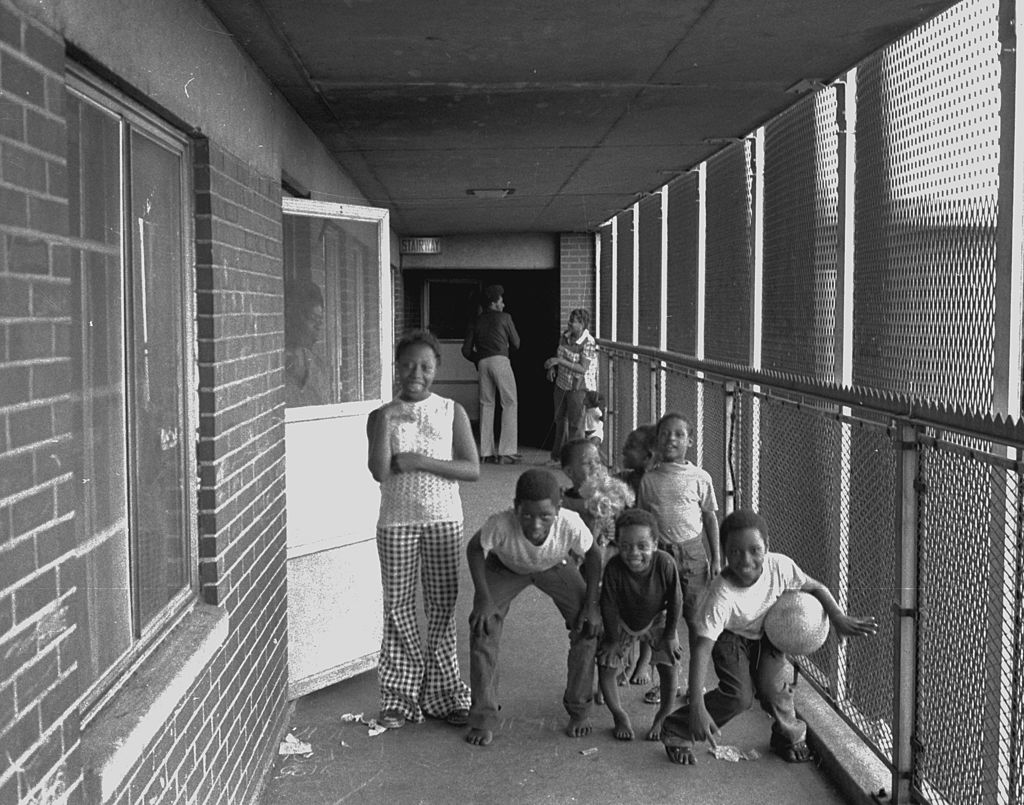

It did in so many ways. You didn’t have streets. You had sort of versions of streets in the sky, the modernist planning principles that Corbusier and other modernist visionaries had attempted. You didn’t have a network of streets where you have eyes on the street, like Jane Jacobs famously wrote about in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. You had what were called galleries. These were breezeways that were in front of long rows of apartments. Those were the streets. And they were fenced in like cages, so that people felt dehumanized.

You had big families in buildings that had minimal elevator service, and invariably you had kids busting the elevators, so people had to trudge up 15 stories where they might get mugged by their fellow residents. You had U-shaped clusters of public housing high rises, and those would serve as shooting galleries. The list goes on and on: all these things that were meant originally as liberating and humanizing elements were flipped on their head because of the concentration of poverty that occurred.

Your Pulitzer was based in part on a series about the lakefront and how it could be improved. What’s your impression of how things have changed since?

I’m really gratified at the changes that have occurred since the series appeared in 1998. The most important changes have to do with Burnham Park, which is south of Roosevelt Road and encompasses the Museum Campus and McCormick Place and the parkland to the south of it. In 1998 that area was separate and unequal. Compared to Lincoln Park in the north, it had less parkland, it had less amenities, it had worse access. Everything about it was worse than the comparable stretch of Lincoln Park to the north. And that was clearly a matter of race. The Chicago Park District followed a policy of so-called benign neglect, because the neighborhoods to the west of Burnham Park were largely poor and Black. And it was an outrageous situation.

Since then, it’s really been corrected. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent to expand the parkland and add new features: fishing piers, a marina, beaches. There are new pedestrian bridges over Lake Shore Drive, replacing the rickety outdated bridges that had been there. Another one is going to start construction this year, I believe at 43rd Street. That’s a really dramatic change. It’s taken 22 years to achieve and the project is still ongoing.

But that’s not the only change that’s occurred as a result of the series. It also looked at Grant Park and its split personality: how it was jammed and vibrant during the summer festivals and pretty much dead otherwise. And since, with the idea of improving daily use as our mantra, there’s been an enormous change within Grant Park. That’s been fueled in large part by Millennium Park and now Maggie Daley Park, but other parts of Grant Park have come alive as well. In those years [since 1998], you think of Lollapalooza — I mean, I’m not taking credit for Lollapalooza, but Grant Park is a much more vibrant place than it was 20 years ago. And that was a key part of the series.

In Lincoln Park, and on other parts of the lakefront, I was really glad to see Ken Griffin spend [what] I believe was $50 million for separating the bike paths and walking paths. That’s a change that I’ve experienced personally, since I ride on the lakefront all the time. The biggest disappointment has been southward. There have been wonderful plans sketched for South Works, but nothing has come of them. And it remains this huge site of huge potential but unrealized visions. I very much hope that in the next 20 years, that will change and that part of the south lakefront will really see the same kind of transformation that Burnham Park has witnessed.

I don’t want to overlook the suburbs. What sort of projects or trends have stuck out to you over the years?

In terms of favorite projects, I’ll give you a list:

- The restoration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple in Oak Park. Spectacular and stirring restoration by Harboe Architects. That was completed just a few years ago and now the temple is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- The Serta headquarters in Hoffman Estates by Andrew Metter, formerly of A. Epstein. That building seems to float beautifully above the landscape in a big corporate office park, and it’s really a little gem that very few people know about, but it’s really worth a look.

- Another favorite is the Writers Theater in Glencoe, by Jeanne Gang. That building really picked up on some of the Tudor revival architecture, exposed wood construction that you see on the North Shore, but Jeanne’s given it her own spin and created a very vibrant center of community where people can gather before and after performances, in a pavilion that’s the visual focal point of the theater. And there’s even a kind of walkway up on the second floor, that as she puts it, exists in between the tree tops, in between the ground and the sky. So that’s a really handsome building.

- Ragdale, Howard van Doren Shaw’s home in Lake Forest, and an arts and crafts gem.

- And then the Cook County Forest Preserves, a legacy of Dwight Perkins. That also was included in Daniel Burnham’s plan of Chicago.

Those are real contributors to the quality of life of people throughout the region. One of the throughlines, besides good design, is a sense of community admidst the less dense environment of Chicago suburbs.

I’m glad you mentioned the forest preserves. That has been an absolute lifeline during the pandemic for my family. [Author’s note: Check out Cook County’s only canyon.]

Yeah, that’s great. Because of the pandemic the forest preserves have taken on fresh relevance. They’re the lungs of the region. We’re truly blessed that we had visionaries like Dwight Perkins and Daniel Burnham.

There have been remarkable leaps forward in how big public parks and spaces, under Daley and Emanuel, fit into cities today. What does it say about them?

In the 20 years that I was the architecture critic for the Tribune, the explosion of new open spaces has been extraordinary. In that period, we saw Millennium Park, we saw Northerly Island, we saw the downtown riverwalk, the 606, and many new parks throughout the neighborhoods. It’s still an ongoing project. There’s still a relative shortage of parkland in the neighborhoods.

But the most important trend has been taking outmoded sites from the industrial age and transforming them into public space. The airport at Meigs Field was no longer necessary, so it’s gone. We decked over commuter railroad tracks in the northwest corner of Grant Park to get Millennium Park. We took a freight line that no longer was in use to create the 606. We moved the highway west of the Field Museum and Soldier Field to create the Museum Campus. All those things represented a realization that many of the planning policies and practices of the 20th century were no longer relevant, and could be reversed by new thinking and new designs.

Millennium Park is a shining example of that. It not only has been an incredible artistic and popular success, but it’s spurred hundreds of millions of dollars of investment and transformed that area of the city. In the past, tourists did not usually go south of the Michigan Avenue Bridge. They stayed on the Mag Mile. The pedestrian flow has really changed. And that’s an indication of the transformative impact of projects like this.

It’s complicated, though, and it’s not an entirely happy story: With the 606, there was the consequence of gentrification. It was great that the shortage of neighborhood public space was addressed with this creative new linear park, and yet, not enough thought was given to the consequences that would provoke, in terms of landlords jacking up rents and displacing the very people that the 606 was supposed to benefit. Doing big infrastructure moves in the neighborhoods is not checkers, it’s chess. You have to think in terms of not just the amenity, but the impact it’s going to have over time. As future 606s are built in places like Pilsen, or on the South Side, their impact is going to have to be taken into account beforehand.

We need to go beyond Burnham’s call for providing humane open spaces as ways to relieve the harshness of the industrial city. In the postindustrial age, we need to think about social and economic realities like gentrification if a truly equitable city is to be built. And that involves going beyond purely physical improvements.

What do you want to see happen next in the city or the region?

Equity is clearly the most important issue that the region faces. During my time as the Tribune’s architecture critic, the middle class in Chicago shrank dramatically as new luxury high rises were built downtown. I’m heartened by the fact that Mayor Lightfoot has started the Invest Southwest program and selected an exemplary planner in Maurice Cox. That program is really trying to turn the aircraft carrier in the right direction.

But it takes a long time to change the direction of an aircraft carrier, and to overcome decades and centuries of discrimination, redlining, all those awful things that have made Chicago such a segregated city. That is really a multigenerational project. I mean, it’s taken a generation to make the lakefront, the most attractive of public spaces, more equitable. Just imagine how long it’s going to take to make the rest of the city, with its deep seated poverty and structural racism, more equitable. It’s going to take a long time, and no one should expect instantaneous fixes. But change can occur. If resources and public resources are losing market investment, dramatic change can occur.

Another [thing I’d like to see] has to do with the environment — not only the built environment, but the air we breathe, ensuring that neighborhoods like those on the southwest side are not viewed as dumping grounds for things like moving the General Iron project out of Lincoln Park. When I speak to the environment, I’m talking about making the region less car dependent, more oriented towards transit. A lot of steps are being taken in that direction by both the City of Chicago and regional planners. I’m hopeful that things are moving in the right direction overall.

What are your personal favorite spaces to be in? Not necessarily the “best,” just what resonates with you the most?

Well, I grew up on the Jersey Shore, and I spent some of the happiest moments of my life body surfing in the Atlantic Ocean off a spit of land called Sandy Hook. It’s a very narrow peninsula that juts into New York Bay and overlooks Lower Manhattan. When I was growing up, you could see the Twin Towers from the edge of this peninsula.

So with that as a backdrop, the space I really enjoy most is the lakefront. It’s this incredibly dramatic meeting of water, parkland, and built topography — the mountains, the cliffs, the canyons of tall buildings that make Lake Shore Drive such a distinctive road and make the lakefront itself such a distinctive place.

There’s very few places like that in the world that have such drama to them, and yet provide such serenity and opportunities to unwind, and unwind with people unlike you, and to see the common humanity. That’s really what I think these public spaces are about: common humanity. So many of us live in silos of zip codes, clustered together with people of similar races or similar economic brackets. Being in these public spaces is a very democratic experience that can, if only temporarily, break down barriers and achieve the kind of democratic aims that people like Frederick Law Olmstead had for public spaces in the in the 19th century.

For me, being on the lakefront is a personal experience that links to my vision of what architecture criticism is about. My role was not simply aesthetic — to be a judge of beauty. It was to look at buildings and public spaces within a framework of how people use them, and whether they give joy or not, whether they uplift us, whether they invite us to form community. I wrote in my final column that I tried to look at buildings not as aesthetic objects or technological marvels, but as vessels of human possibility.

Comments are closed.