Asian carp—which leap into the air when startled by a motor—bombard boaters on the Illinois River, where by some estimates they have replaced up to 95 percent of native fish.

Related:

Superstar architect and MacArthur Fellow Jeanne Gang on a potential solution to the Asian carp problem »

Superstar architect and MacArthur Fellow Jeanne Gang on a potential solution to the Asian carp problem »

PLUS: Hear Gang talk about her visionary plan for the Chicago River at a panel (led by Chicago editor Geoffrey Johnson) at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (2430 N. Cannon Dr.; 773-755-5100) on December 7 at 7 p.m. For more information, go to naturemuseum.org.

The deluge descended in the hours before dawn, nearly seven inches of rain that saturated the city—the heaviest single-day downpour since Chicago began keeping records in 1871. So biblical was that rainfall last July 23 that the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District made a drastic decision. It opened the locks downtown on the Chicago River and up north at the Wilmette Pumping Station, spewing 2.2 billion gallons of storm water and wastewater into Lake Michigan. “The action was taken to prevent overbank flooding along the waterways,” says Ed Staudacher, a supervising civil engineer with the district, calling it “a last resort.”

Though the locks were open by 3:30 a.m., some parts of the city got flooded anyway. In the Norwood Park neighborhood on the Northwest Side, for example, the streets turned into rivers, water pouring into cars parked along them. The foreign exchange student staying in Claudia Niersbach’s finished basement woke her in the middle of the night. Downstairs she found water shooting up through the floor “like a geyser.” Still, Niersbach was one of the fortunate ones: Because her house sits on a hill, it suffered only minor damage. “Our neighbors weren’t so lucky,” she says. “Water was coming in through their doors. They had to throw everything out.”

Two weeks later and 210 miles southwest, in the little town of Bath, Betty DeFord was fighting her own aquatic battle. DeFord manages Boat Tavern, which sits along the banks of the Bath Chute, a branch of the Illinois River. The bar serves as headquarters for DeFord’s annual Redneck Fishing Tournament. She began the popular two-day event in 2005, after she and her grandchildren were attacked on the river by fish that looked to her husband, Kenny, like mutated shad. “I thought they were going to sink our boat,” she recalls. “The fish were jumping out of the river like popcorn popping. We had to beat them off with an oar and a broom. We ended up with 32 in our boat. It was very, very scary.”

Those fish, of course, were the invasive Asian carp. The 1,000 or so participants in this year’s tournament netted 8,977 of them—a tiny fraction of the roughly 1 million that infest the Illinois River. “I have a personal vendetta against those stupid carp,” says DeFord. “Our community’s summertime activities are watersports. But it has gotten too dangerous to take our grandkids out there.”

What’s the connection between Claudia Niersbach’s flooded basement and Betty DeFord’s fishing tournament? The 111-year-old engineering marvel known as the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (see “Sunken Treasures: Rediscovered Photographs of Turn-of-the-Century Chicago”). That 28-mile ditch, which reversed the flow of the Chicago River, connects Lake Michigan and the Chicago River to the Illinois River and thus to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. The canal serves three main functions: carrying the city’s sewage to points south, acting as an escape hatch for heavy rains, and providing an avenue for commercial shipping. But the canal is increasingly overwhelmed by intense storms, which are likely to become more frequent as a result of global warming , according to a report prepared for the Chicago Climate Action Plan. What’s more, the canal lays out a watery welcome mat for the Asian carp, which are now at the very edge of the Great Lakes.

The battle over what to do about this looming invasion is heating up. On one side: 17 states, the province of Ontario, the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, and numerous environmental organizations, including the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). On the other: the City of Chicago, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, the State of Illinois, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and businesses from as far away as New Orleans. Watching from the sidelines are outdoorsmen, homeowners, and taxpayers, all worrying about the future of the Great Lakes, the water streaming out of their taps and/or into their basements—and the astronomical size of the bill that might one day await them.

When the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal opened in January 1900, most Chicagoans agreed that it was a boon. Until the canal’s completion, raw sewage and effluent from the city’s tanneries, factories, and slaughterhouses got dumped into the Chicago River. From there it flowed into Lake Michigan, the source of the city’s drinking water. But the canal—considered the eighth wonder of the world in its day—sent all that nasty stuff south, where it would be somebody else’s problem. It helped eradicate the threat of cholera, typhoid fever, and other deadly waterborne diseases, allowing the city to prosper.

After further improvements in the 1920s and 1930s, the canal also yielded significant commercial benefits. It created a thoroughfare for ships to travel up from the Gulf of Mexico, through Chicago, and into the Great Lakes. With the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, that aquatic highway extended all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, and Chicago became (at the time) the fifth-largest port in the nation.

But if the canal was a boon, it was also a battlefield, even before it opened. None too happy about all that liquid waste headed its way, the State of Missouri mounted an immediate legal challenge. Though it ultimately lost that case in the U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for the majority, sounded a note that still resonates a century later. “It is a question of the first magnitude,” he wrote, “whether the destiny of the great rivers is to be the sewers of the cities along their banks or to be protected against everything which threatens their purity.”

Fast-forward to 1973. That year, Jim Malone, an Arkansas fish farmer looking for a way to control the growth of aquatic weeds, imported various carp from Asia. Malone kept the grass carp but gave two other species—silver and bighead—to the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, which began breeding them. Bug-eyed, corpulent, and voracious, the fish gobble up just about anything green, eating from 5 to 20 percent of their body weight in a single day. (Silver carp—the prodigious jumpers that terrified Betty DeFord—can reach 40 pounds; bigheads can top 100.)

Though no one knows exactly how, some of those carp got into public waters. In 1980, a commercial fisherman caught several silver carp in a creek about 45 miles southeast of Little Rock. In the decades that followed, the fish made their way from the Arkansas River into the Mississippi and then into the Illinois, advancing at the rate of about 35 miles a year. They reproduced obscenely fast, crowding out other species. “The population in the Illinois River is higher than anywhere else in the world, including China,” says Kevin Irons, manager of the aquaculture and aquatic nuisance species program for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. By some estimates, Asian carp have replaced up to 95 percent of the native fish population.

Photograph: Nerissa Michaels/AP

Related:

Superstar architect and MacArthur Fellow Jeanne Gang on a potential solution to the Asian carp problem »

Superstar architect and MacArthur Fellow Jeanne Gang on a potential solution to the Asian carp problem »

PLUS: Hear Gang talk about her visionary plan for the Chicago River at a panel (led by Chicago editor Geoffrey Johnson) at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (2430 N. Cannon Dr.; 773-755-5100) on December 7 at 7 p.m. For more information, go to naturemuseum.org.

One of the first local leaders to recognize that something needed to be done was Mayor Richard M. Daley. In May 2003, he and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service convened the two-day Aquatic Invasive Species Summit in Chicago. The carp were about 55 miles from Lake Michigan.

As luck would have it, just the year before, the Army Corps of Engineers had completed an electric barrier on the canal near Romeoville. Its original purpose was to repel yet another finned menace: the mollusk-munching round goby, a Eurasian native, which was moving south from the Great Lakes. (The electric barrier functions like an invisible dog fence: creatures approaching it receive a shock that, theoretically, keeps them from advancing.) Unfortunately, by the time the barrier was up and running, the goby had already slipped by. But at least the barrier could stop the carp from going north, right?

Wrong, concluded the 60-plus experts who had traveled from around the world to attend Daley’s conference. They worried that the barrier wasn’t reliable enough to keep the carp out. There was, the attendees concluded in a postconference report, only one “essential” solution: “Completely separate the waters of the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins by creating a physical or other type of barrier in the Chicago Canal System.” Without such a move, the experts foresaw “irreversible damage to these remarkable ecosystems.”

Amid corporate and government fears about the economic impact—an estimated $16 billion in cargo annually travels through the Chicago Area Waterway System—not much happened. The Illinois DNR did what it could—for example, hiring fishermen to catch carp in the Illinois River. Last summer, the DNR hauled in 240 tons of carp, which was turned into fertilizer; commercial fishermen caught tons more, most of which were shipped to China under an agreement signed in July 2010 by Governor Pat “If You Can’t Beat ’Em, Eat ’Em” Quinn. But that wasn’t enough to quell the threat. (Mayor Rahm Emanuel declined to comment for this article.)

Rather than rethinking electric barriers in the wake of the experts’ warnings, the Corps of Engineers kept building more. There are now three on a 1,150-foot-long span of the canal, all near Romeoville, all designed, built, evaluated, and maintained by the corps at a cost thus far to taxpayers of about $75.4 million.

* * *

In the fall of 2009, David Lodge made an unsettling discovery. The director of the Environmental Change Initiative at the University of Notre Dame, Lodge had been hired by the corps to help assess the carp threat. He soon realized that the corps did not seem to know exactly how far toward Lake Michigan the fish had traveled. “If you don’t know where they are, you can’t fight them,” he says. “It occurred to us that, rather than capture the fish [as the corps had been doing], maybe we could figure out where they were using indirect genetic means.”

With his colleagues, Lodge began collecting water samples from the canal and testing for environmental DNA, or eDNA, cellular material the carp had left behind. “We did not expect to see evidence of the carp north of the electric barrier,” Lodge remembers. “We were astonished and very disappointed to find it there.”

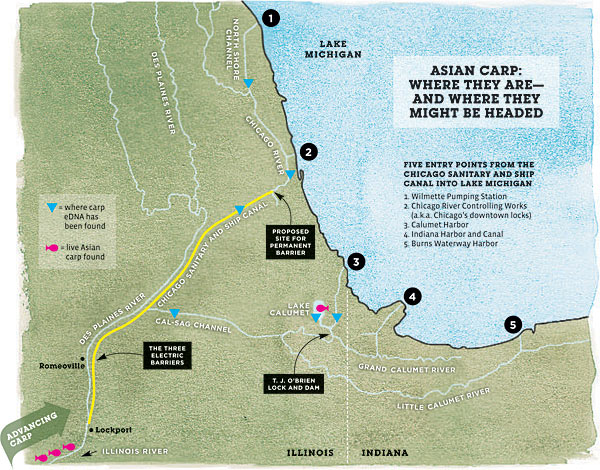

In November 2009, state and federal officials announced that eDNA evidence of the Asian carp had been found on the Calumet River near the T. J. O’Brien Lock and Dam, more than 20 miles above the barrier (see map, page 94). (In addition to that lock, water from the canal passes into Lake Michigan via four sources: the Wilmette Pumping Station; Chicago’s downtown locks, officially known as the Chicago River Controlling Works; the Indiana Harbor and Canal; and the Burns Waterway Harbor in Indiana.)

To Henry Henderson, Midwest program director for the NRDC, discovery of carp eDNA past the electric barriers is proof that “the barriers don’t work.” Lodge agrees. Because DNA decomposes quickly, he rules out the possibility that the eDNA arrived in the river after passing through the digestive system of a bird or human who had consumed the carp. Other scenarios seem equally unlikely. “All the evidence that exists points to the most plausible explanation for the positive DNA findings,” Lodge says. “There are Asian carp above the barrier.”

Don’t tell that to John Goss, President Obama’s so-called carp czar (he heads the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee, which comprises 21 local, state, and federal agencies). “Right now, there’s a lot of uncertainty about what traces of eDNA mean,” says Goss, who formerly worked at the Indiana Wildlife Federation. “We don’t know if it’s evidence of a live or a dead fish or if it comes from fish scales or from a barge [traveling in the Chicago canal]. We need further research.” He adds: “All evidence shows that we are succeeding in keeping Asian carp out of the Great Lakes.”

The Illinois DNR, for its part, took Lodge’s news very seriously. Within days, its biologists poured 2,200 gallons of the fish toxin Rotenone into a six-mile stretch of the canal below the barriers. The operation yielded between 30,000 and 40,000 dead or surfaced fish; only one of them was an Asian carp, and it was found five miles below the barriers. A month later, commercial fishermen hired to search for carp above the barriers netted a three-foot bighead in Lake Calumet—a worrisome development, especially since officials couldn’t say how it got there. Over the next 11 days, fishermen deployed ten miles of nets in Lake Calumet and captured more than 15,000 fish. None of them were an Asian carp.

Related:

PLUS: Hear Gang talk about her visionary plan for the Chicago River at a panel (led by Chicago editor Geoffrey Johnson) at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (2430 N. Cannon Dr.; 773-755-5100) on December 7 at 7 p.m. For more information, go to naturemuseum.org.

Meanwhile, Illinois’s neighbors weren’t waiting around—they were heading to the courts. Led by Mike Cox, Michigan’s attorney general, several states (including Ohio, Wisconsin, and Minnesota) sought the immediate closure of the two Chicago-area locks to protect the $7 billion Great Lakes fishing industry. Cox initially sought a hearing in the U.S. Supreme Court, which repeatedly rebuffed him, for reasons it declined to explain. But in a memo, Elena Kagan, now an associate justice on the court but in early 2010 the solicitor general, argued that, given the potentially huge negative impact to businesses and public safety, there was insufficient evidence to warrant closing the locks.

Cox did get a hearing in the district courts, where he asked for a preliminary injunction to close the locks. Judge Robert M. Dow Jr. ruled in December 2010 that Michigan and its allies had failed to demonstrate that “the potential harm [to the Great Lakes was] either likely or imminent.” (Though Cox is no longer Michigan’s attorney general, his quest for a permanent injunction is still in play; it’s unlikely to go before a judge any sooner than late 2012, if then.) In August, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed Dow’s decision, though it left the door open for the district court to “revisit the question.”

That kind of language keeps Mark Biel awake at night. The executive director of the Chemical Industry Council of Illinois and chairman of the trade group Unlock Our Jobs, Biel worries that closing the locks or installing a permanent barrier would be an economic nightmare for companies that rely on traffic through the canal. “I’m not saying [the carp threat] isn’t something to be concerned about,” he explains. “But with 18 pathways into the Great Lakes, the canal is the one that’s guarded like Fort Knox. If carp get into the Great Lakes, it’s not going to be through the Chicago water system.”

Indeed, a more vulnerable spot may lie 165 miles southeast of Chicago, near Fort Wayne, Indiana, in a 705-acre wetland called Eagle Marsh. During a flood, the marsh could link the Wabash River, where the carp are present, and the Maumee River, which flows into Lake Erie—a possibility that last year prompted the Corps of Engineers to install mesh fencing across a section of the marsh.

The corps has also launched a comprehensive study to assess threats to the Great Lakes and Mississippi watersheds from all invasive species and lay out a plan to counter them. The study’s scheduled release date: 2015. Dave Wethington, the study’s project manager, says that much time is necessary to resolve such a complex issue. In the meantime, he points out, the corps continues to man its electric barriers, monitor the waterways, and consider other methods—such as underwater cameras and sonic cannon—to track and repel the carp.

“We’re fiddling away time,” says the NRDC’s Henderson, frustrated. His organization is looking for a solution of its own. Last year, it released a report advocating the same remedy proposed by the experts at the 2003 conference: Replace the natural barrier between the Mississippi and the Great Lakes that was breached by the canal.

If only it were that simple. “You can’t look at the barrier issue without looking at flood control, water quality, and transportation,” insists David Ullrich, who, after 30 years with the Environmental Protection Agency, now serves as the executive director of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative. Sure, no one wants Asian carp in the Great Lakes. But no one wants contaminated water in the coffeepot either. Or rainwater—or sewage—pouring into the basement. Or higher taxes.

* * *

So, you may be asking yourself, what’s the worst-case scenario if we let the carp frolic in Lakes Michigan, Erie, et al.? Pretty bad: Crucial phytoplankton and other microorganisms (an integral part of the lakes’ food chain) picked clean and replaced by algae that could strangle those inland seas. Fishing of native species—for fun or for profit—destroyed. No more water-skiing (boat motors send the carp flying). And that’s just for starters.

The best-case scenario would be that the Great Lakes prove inhospitable to carp. “The waterways here are not really a conducive environment for them,” says David St. Pierre, the executive director of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, who, granted, may be a little biased. But nobody really knows either way.

And what if a permanent barrier is put in place—essentially undoing the awesome century-old work of those visionary Chicagoans? The likelihood of flooding and tainted tap water might increase. And the cargo-laden barges and recreational boats, which rely on freely navigable Chicago waterways, would find their travel impeded.

No study has projected the economic effects (and the corps has declined to hazard a guess). But in 2010, Joseph Schwieterman, a public service management professor at DePaul University, estimated the cost of closing the two Chicago-area locks at $1.3 billion a year. That doesn’t include the impact of lowered tax revenues, lost employment opportunities, or the diminished value of the properties along Chicago’s waterways.

Nor does it include the cost of implementing and maintaining the waterway separation. That could vary widely, depending on what gets built. For example, the NRDC solution includes a plan for pumps that would send water pouring across the barrier (after it had been screened for any invasive organisms). That means the river would continue to flow away from Lake Michigan, lessening the potential for flooding or tainted water resulting from the project. NRDC spokesman Josh Mogerman says that the system might cost between $80 million and $120 million.

Should the flow of the Chicago River actually be re-reversed—another option—costs would skyrocket. That’s because city officials would have to remove all the heavy metals and other industrial waste on the bottom of the river before they could think of sending the water, once again, back into Lake Michigan.

In the meantime, we wait. And Betty DeFord plans next year’s fishing tournament. “You can see all the pictures and YouTubes you want,” she says, “but until you experience the carp firsthand, you have no idea what they’re like. You don’t want these fish where you live.”