Before I learned to love restaurants, I learned to love reading about them. My mom, a faithful Bon Appétit subscriber, meticulously kept a multiyear archive of back issues on a shelf in a closet near our kitchen. Every so often, we would go through them together, cutting out recipes to save on index cards before tossing the old magazines.

While doing that, I discovered RSVP, a regular column where readers would write in requesting recipes for favorite dishes at restaurants they’d visited. I can remember indexing the most delicious-sounding ones in my head, creating a mental atlas of places I dreamed of visiting someday. Soon interest grew into a fixation. By the time I was 7 years old, I had picked up the extremely normal hobby of reading restaurant reviews in the local paper each week. It surprised no one when I went on to become a food writer.

The pandemic has necessitated a significant shift in how restaurants are written about, and often the news that journalists have to share is difficult. For a brief hit of pleasure, I have turned instead to reading about restaurants of the past in order to avoid thinking about those of the present. And it is through this nostalgic exercise that I discovered Duncan Hines.

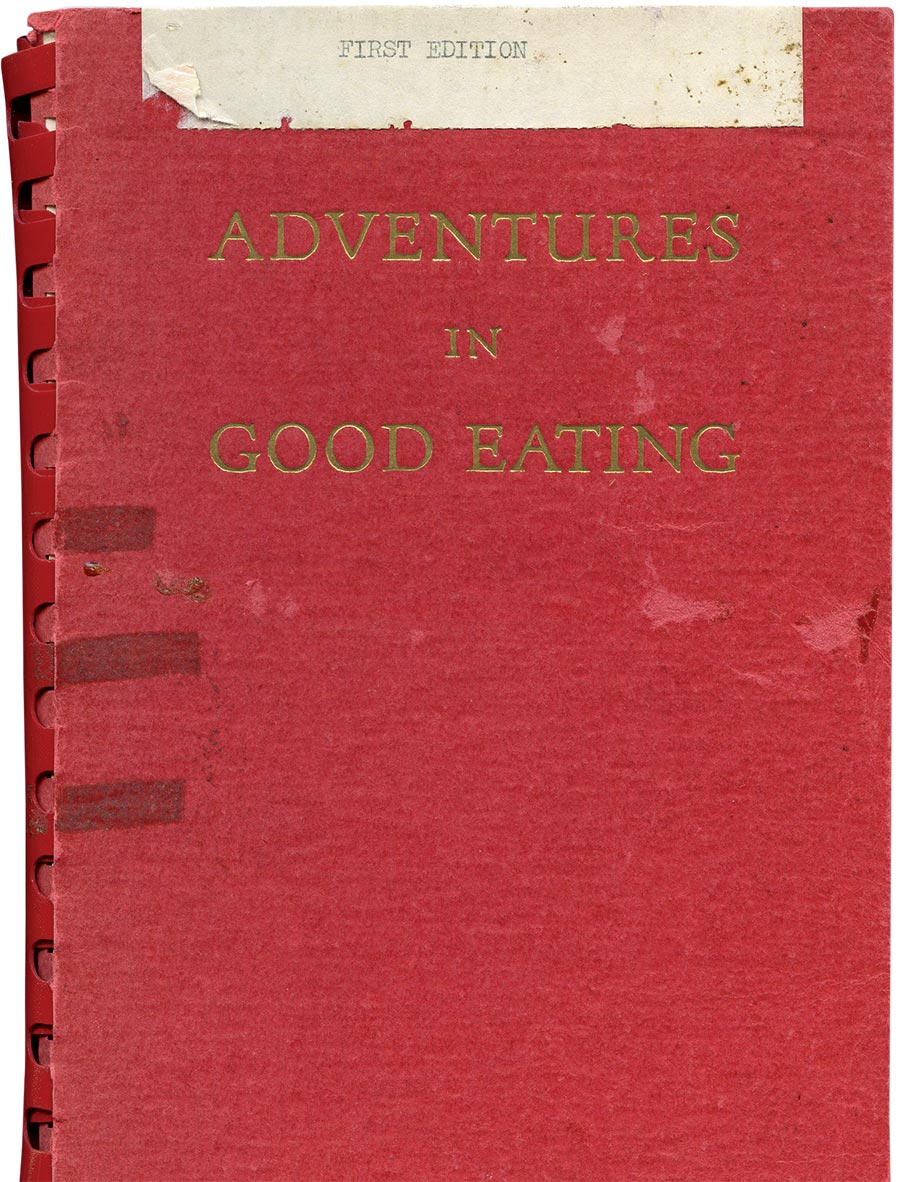

Yes, the Duncan Hines of boxed-cake-mix fame. It turns out he was a vital figure in food-writing history, having published more than 25 annual editions of a best-selling restaurant guidebook during the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. Adventures in Good Eating, as the compendiums were called, contained pithy recommendations for travelers to thumb through before making a pit stop for a meal.

The reviews were written in a no-nonsense Midwestern parlance that occasionally verged on corny. “If you’re against cruelty to vegetables and like your meats well treated too, try Keeney’s,” he wrote of a cafeteria in Wooster, Ohio, in the 1945 edition. Of a spot in Michigan called the Islington, he remarked, “In the pine-scented north where there is no hay fever and plenty of fun. Good food is an added attraction. Their whitefish is very good!” As his readership grew, he started selling seals of approval that the restaurants he had recommended could proudly display in their windows. He was, in some ways, America’s first food influencer.

Like fellow 20th-century epicures Julia Child (a diplomat’s wife) and James Beard (an actor), Hines didn’t set out to be a food writer. He and his wife, Florence, came to Chicago in 1905, and he took a job in advertising. Working out of an office in the Marquette Building in the Loop, he quickly became a top salesman, thanks in part to his willingness to hop in the car or on a train to attend to clients in, say, Ohio and then turn right back around once he was done.

During these business trips, he began keeping a journal of places he’d enjoyed dining at, noting their addresses, hours, and bills of fare. Before long, he started doing the same on weekend “motoring” vacations with Florence across the Midwest. From the early 1920s to the late ’30s, they covered between 40,000 and 60,000 miles together each year — this in addition to all of Hines’s business travel, which started to look more and more like culinary excursions. Once, Hines got embroiled in a conversation about lobster with a couple of friends who insisted that New England lobsters were the best. A few weeks later, Hines and his wife were in the back seat of these friends’ car on the road to Maine.

Hines’s travel notebooks became the stuff of legend, and soon enough any Chicago salesman who knew his stuff would call Hines before setting out on the road, asking for dining recommendations at his destination. By the mid-1930s, Hines was sick of fielding constant calls. So in 1936 he decided to publish the first edition of Adventures in Good Eating.

Though similar guides existed at the time, Hines believed he offered something unique. While other publications delivered favorable reviews in exchange for advertising dollars, Hines prided himself on never accepting a free meal, though he did apparently accept gifts — in one case, a Cadillac — from restaurateurs he’d already favorably reviewed. He loved showing up anonymously; he made reservations under fake names, and he purposefully chose an old photo of himself to accompany his author bio so restaurateurs couldn’t spot him in their dining rooms. The only company doing anything similar to his food-travel guides at the time was a tire manufacturer in France called Michelin.

Despite once claiming that he “would like to be food dictator of the U.S.A. just long enough to padlock two-thirds of the places that call themselves cafes or restaurants,” Hines was no gourmand. Even after years on the road, the man’s favorite cocktail was an unholy mixture of gin, grenadine, an egg, honey, and pickled-watermelon juice, and he often bragged of being able to drink a dozen of these in a sitting. Judging from the meals described in his books, his palate tended toward simple food, at both roadside spots and high-end hotels.

Indeed, far from considering himself an arbiter of gastronomic taste, he conceived of his project as a noble attempt at protecting the lives of his fellow salesmen. In an era when health inspections were less than rigorous, there were more than a few horror stories circulating among traveling types about unlucky diners getting a bad meal on the road and dying of food poisoning. So, basically, Hines was chronicling establishments that served decent-tasting food that wouldn’t kill you. He was so obsessed with the not-killing-you part that he insisted on inspecting the kitchen of any restaurant he was considering for his guide to ensure it was clean enough to recommend.

Hines became famous for Adventures in Good Eating — so famous, in fact, that by the time he stopped actively writing reviews, sometime in the 1950s, he had licensed his name to several food products. Those products, in turn, became famous too, and now his legacy rests not on his restaurant reviewing but on boxes of devil’s food cake mix.

Hines saw going to restaurants as a particularly appealing kind of leisure sport, and I suppose I do too. The way some people get really into golf, I get really into dessert menus. Now, with COVID-19 keeping us indoors, I miss the act of recreational dining all the more, of setting forth on a couple of hours’ adventure with the hope of having something interesting and good to say about it afterward. And I miss reading about the similar adventures of others. These are stories that keep a certain promise alive: that the next great meal is just ahead.

Comments are closed.