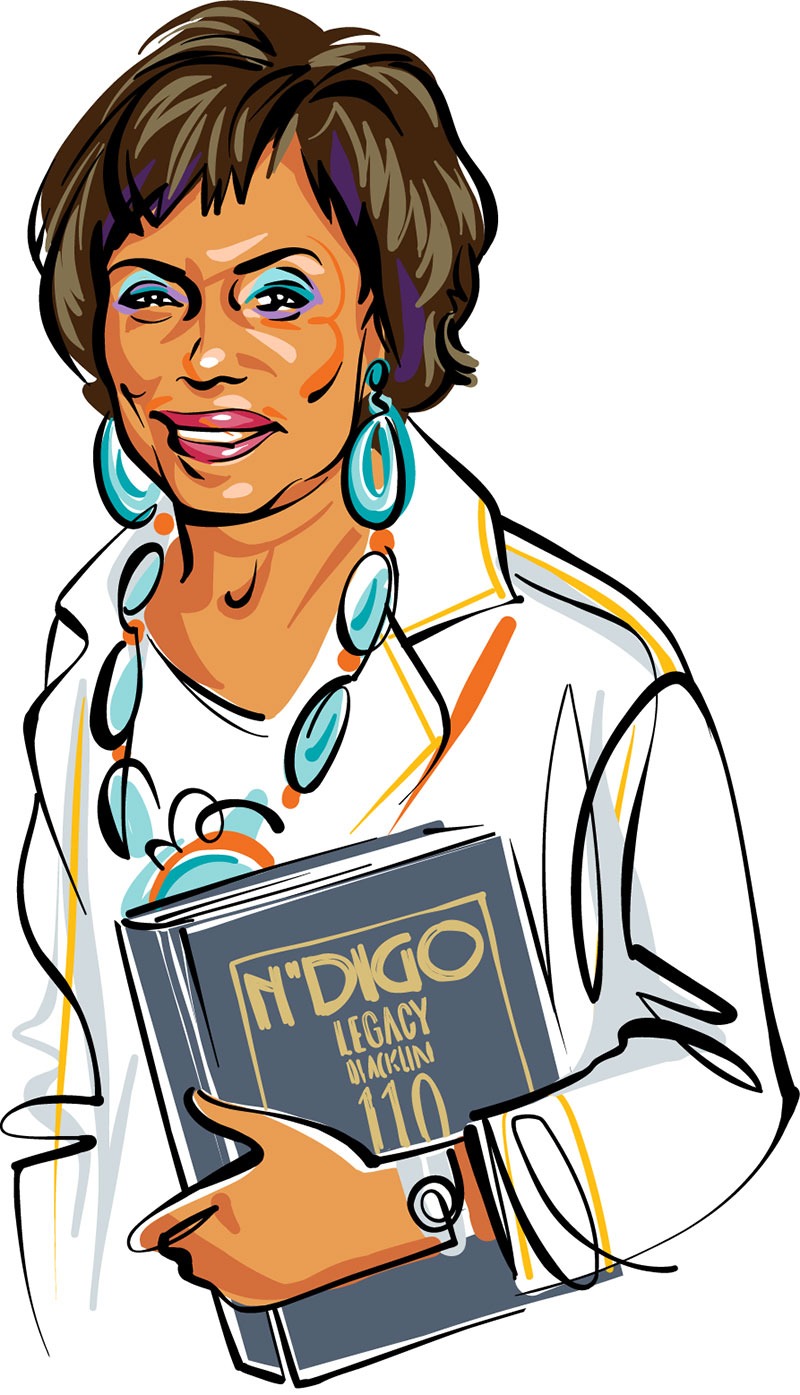

■ N’Digo was for the cosmopolitan, urbane, metropolitan dweller. We blanketed the city with this “magapaper,” because I was trying to change the narrative on Black folk in Chicago. My first editorial in the very first issue, in 1989, was about why we would capitalize the B in “Black.” When they didn’t capitalize the N in “Negro,” W.E.B. Du Bois had to write letters to say, “Would you please recognize us as a full people?” So it was overdue. The mainstream media just caught up.

■ My father was the first Black Pepsi distributor in America. He was from Houma, Louisiana, and lived in Chicago from when he was like 12. He called the Great Migration the Great Escape. My mother, who is half white, has been in Chicago since she was a baby and didn’t know anything about the South. She got in trouble once when she went to New Orleans. She was told to sit at the back of the bus, and she said, “Why? I paid my fair share. I want to sit here.” She caused quite a ruckus.

■ My uncle, the jazz singer Johnny Hartman, lived in New York, where he recorded and played in clubs. He was also quite the chef, so when he came home to Chicago, whoever was in town was at our table for Sunday dinner. It could be Bill Cosby or Dick Gregory or Miles Davis. My uncle was a huge influence on me in terms of creativity and not worrying about what other people say. And I think my love of words comes from him. He would constantly say, “Listen to these lyrics. What do they say?”

■ My mom went to the beauty salon across from Jesse Jackson’s Operation Breadbasket offices on 47th Street. She would say, “This is something you should be involved in.” I was very shy, but I typed 125 words a minute and was learning filing and dictation at Jones Commercial High School. So I went into the offices every single day after school for one week. Nobody paid attention to me. I told my mom, “I’m not going there anymore.” She said, “You’ve got to make yourself known.” So I went in on Saturday, introduced myself to Jesse, and gave him a laundry list of what I could do. I ended up working with Reverend Ed Riddick, doing research and statistical analysis. He was a genius. I learned more from him than in any class.

■ Quincy Jones was a dear friend. David and I lived with him the summer before we got married, while working on a fundraiser for Reverend Jackson. He talked to us about interracial marriage. He said, “Just do what you do. Don’t worry about others — the real friends will be there.” Once, David was picking me up from school at Roosevelt and some Black Panthers insulted me for being with a white guy. I was quite angry. The next day they beat me to the car and were chatting with David about political strategies and doctrine. When people begin to see each other as people, based on interests and concerns, the race thing usually diminishes.

■ A Barack Obama editorial I wrote, where I said the president is not loyal, got me in hot water. When he lived in Chicago, he would call me every Monday morning about being on the cover of N’Digo. And I finally did it, because I saw the promise of a budding politician. And I can’t tell you how I beat up some of these guys to give Barack real campaign money — $50,000 or $100,000. Then when he gets to the White House, he don’t know them no more? People said, “How dare you criticize the first Black president of the United States?” With Black folks, when we get to a certain height, there’s a belief that you don’t criticize each other publicly — it took us too long to get here. Well, really? I’m not of that school of thought. I’m going to say it like I see it.

■ The older I get, the smarter my gut becomes. It’s real smart right now.