As the son of Jewish parents—one an American, the other an Iraqi immigrant—Michael Rakowitz grew up in a house of contradictions in Long Island, New York. It wasn’t uncommon to feast on dolmades and kebab during Jewish high holidays. “[Our traditions] were Jewish,” says Rakowitz, “but also very clearly Arab Jewish.”

Rakowitz didn’t think too much about his unusual heritage until a visit at age 10 to the British Museum in London, where his mother showed him a gallery of ancient Assyrian art. “She said, ‘This is from the place your grandmother and I are from,’ ” recalls Rakowitz. “I was mind-blown. It was a link to our past.”

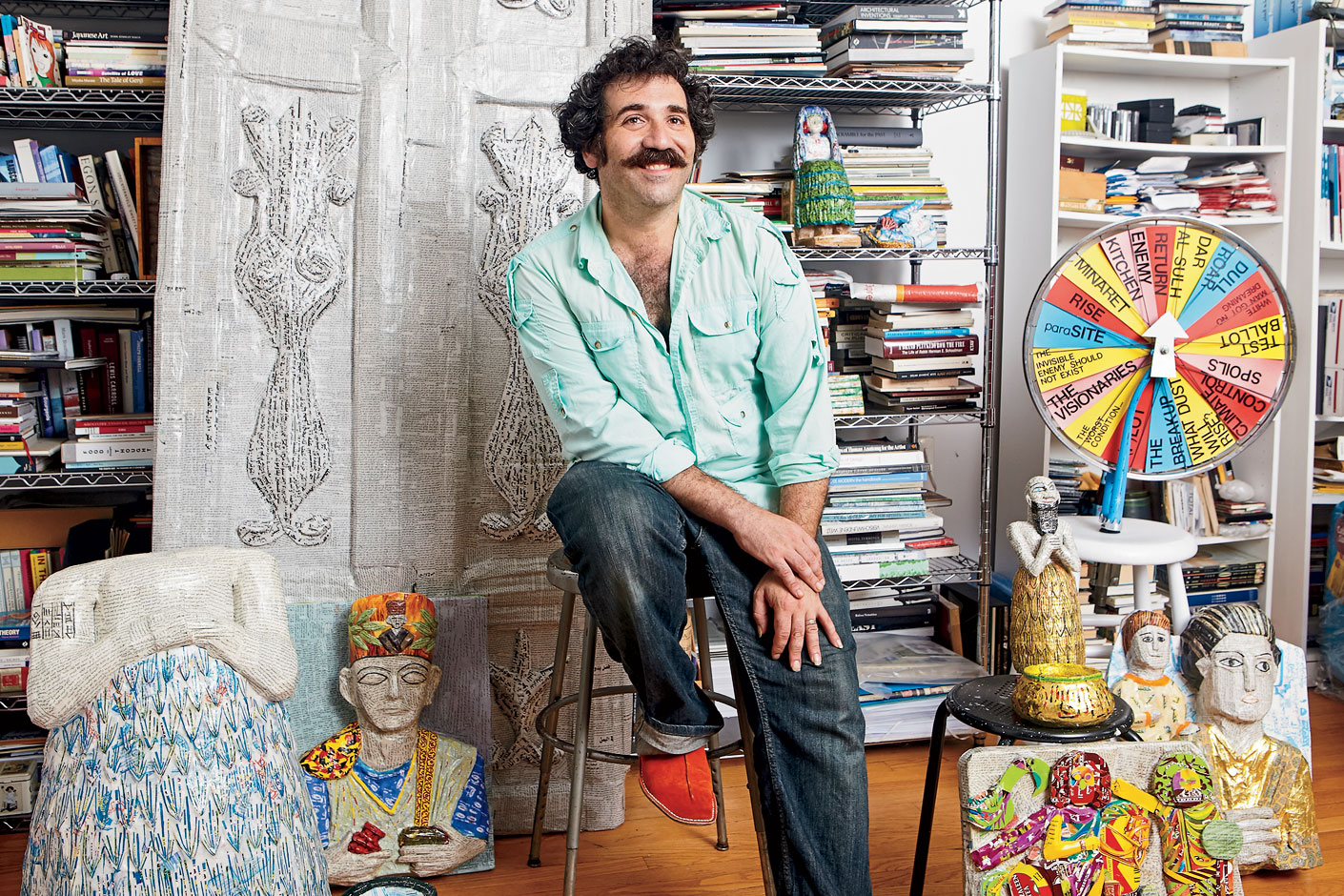

Now a Northwestern professor and internationally acclaimed sculptor whose work has been shown at the prestigious art exhibition Documenta and in New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, Rakowitz, 43, has built a career exploring his identity through his craft. His most ambitious project, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, is an ongoing attempt to reconstruct all 7,000 artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, using Middle Eastern newspapers and food packaging. So far Rakowitz has finished 700, 40 of which are part of his first major U.S. solo exhibition, Backstroke of the West, at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

“It all goes back to my mother and grandmother,” he says. “So many of my projects are wrapped up in a desire to keep family stories of Baghdad from disappearing.”