In 1958, When Riva Lehrer was born with spina bifida — a congenital disorder that causes the spinal cord to partially protrude from the body — the diagnosis was usually a death sentence. Fortuitously, her mother worked for Josef Warkany, the father of experimental teratology (the study of birth defects), and found a surgeon to push Lehrer’s spine into place. This would be the first of dozens of invasive medical procedures promising a so-called normal body — and, with it, acceptance and inclusion.

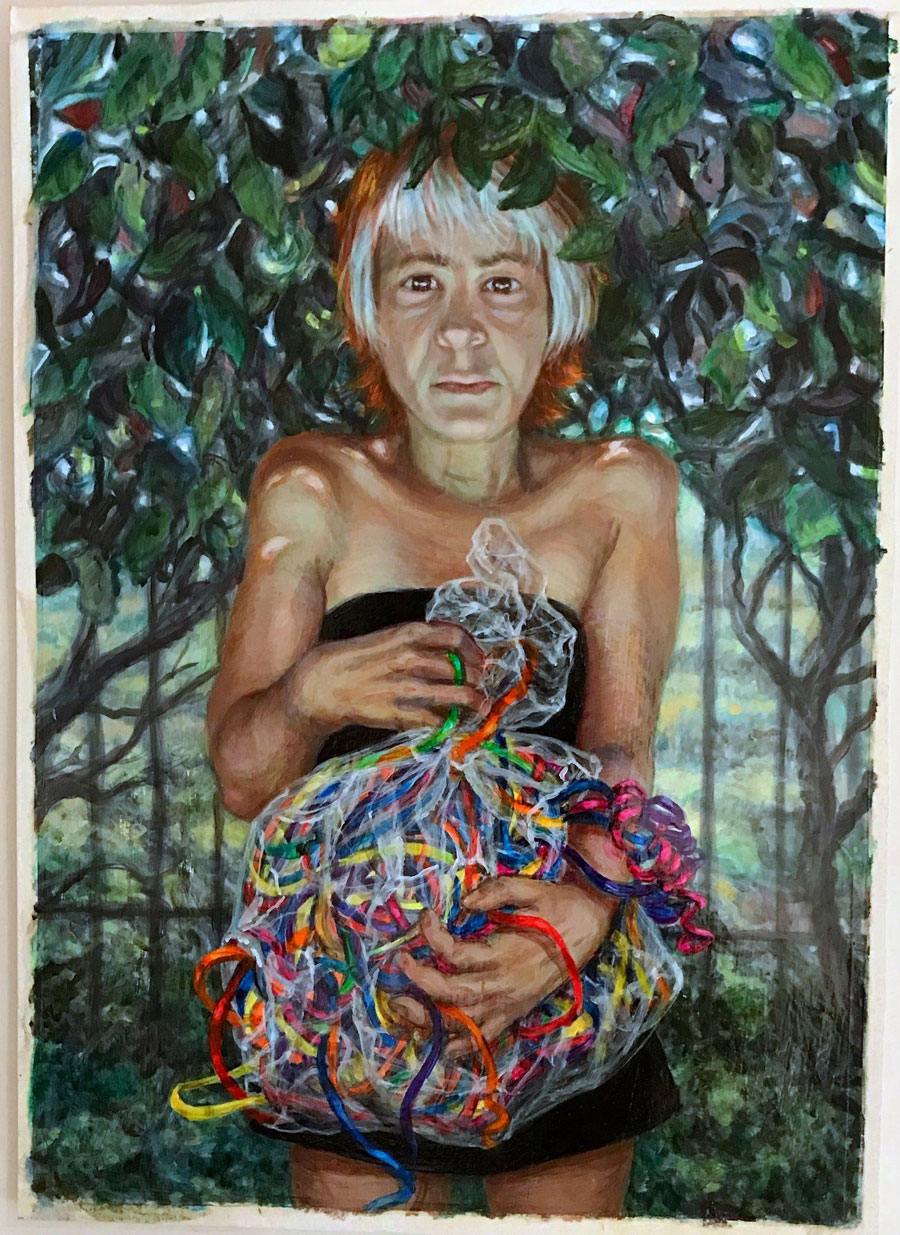

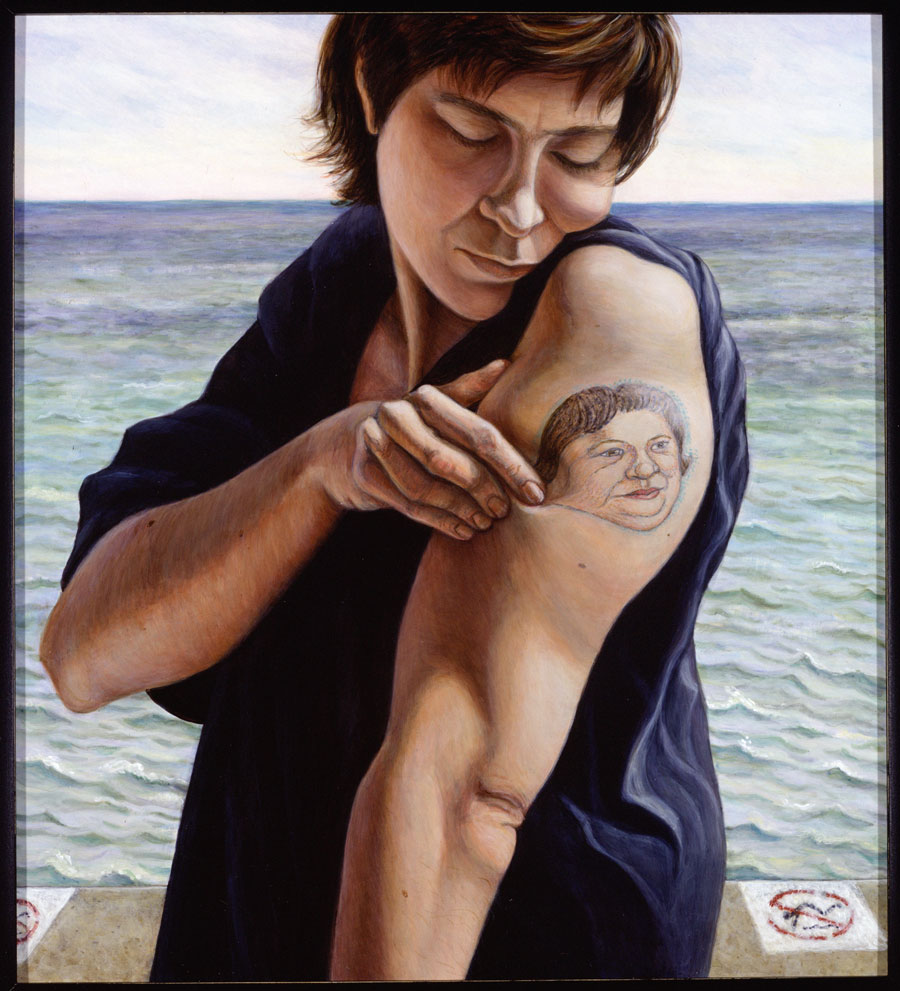

Today, Lehrer, 62, is best known for her striking portraits, mostly in acrylic and charcoal, of queer and disabled people. Their bodies, along with adaptive devices like wheelchairs, are presented without spectacle. Lehrer is also known for her process, which she describes as “extreme consent”: She’ll leave her subjects alone in her studio and permit them to make their own contributions to, and even destroy, her portraits of them. In this way, she takes people off the examination table and allows them to be actors in their own portrayals.

In Golem Girl (out October 6), Lehrer turns her gaze on herself. Her memoir intersperses reproductions of her paintings with an account of growing up queer and disabled as society's understanding of those identities continuously changed. Her stories about attending a school for disabled children and her first attempts at sex are engaging enough, but what stands out is Lehrer’s ability to make connections — between her story and her mother’s, among cycles in her own life, and within her peer groups. The result is like artworks on translucent paper: In the foreground is Lehrer's portrait of herself, and through it can be seen those of the people whose stories contributed to her own.