In 1982 a magazine article turned criminology on its head: "Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety," by two social scientists, George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson. As the subtitle suggests, the article focuses on policing, and "broken windows" theory became an influential and controversial approach—in ways Kelling and Wilson didn't intend—emphasizing the maintenance of order in neighborhoods with crackdowns on minor crimes that's become synonymous with fears of over-policing.

I've idly wondered if there was more to the "broken windows" metaphor itself. What about actual, you know, broken windows? Set aside policing—what if you focused strictly on physical disorder?

There's some interesting evidence for this. In 2005, researchers at Harvard and Suffolk University cleaned up messes, changed policing strategies, and bumped up mental-health and homelessness referrals in crime hot-spots in Lowell, Massachusetts, while leaving others as controls. In the treated areas, calls to the police dropped 20 percent. "Cleaning up the physical environment was very effective; misdemeanor arrests less so, and boosting social services had no apparent impact, the Boston Globe reported.

These idle thoughts about broken windows and crime came back when I learned about a new study by Hiroki Kotabe, a post-doctoral student in the lab of University of Chicago professor Marc Berman, whose research on the psychological effects of the physical environment I've written about before. It's called "The Order of Disorder: Deconstructing Visual Disorder and Its Effect on Rule-Breaking," and it's inspired in part by the broken windows idea.

"The research on broken windows theory has taken a very high-level view: they've been talking about all these social cues and how people reason consciously about these social cues," Kotabe says. "I was interested in whether the very early processes also contribute to the effect—the early processes of perceiving physical features in the environment, whether that can actually relate to rule-breaking."

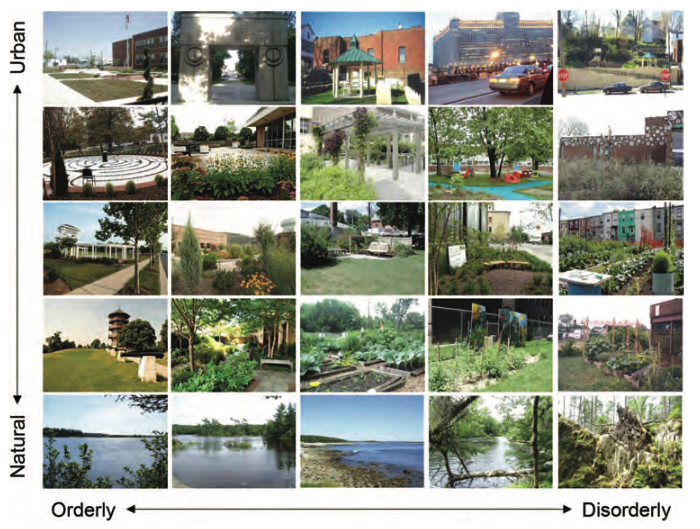

In other words, Kotabe tried to get at a more fundamental level of disorder than something as obvious as actual broken windows. So he and his colleagues began with 260 scenes, and had participants rate them on how disorderly they looked. As you can see from a selection of the scenes, even those rated as disorderly were not necessarily clichés of disorder. You probably will recognize one of them, in the top-right quadrant: it's Wacker Drive looking at the Merchandise Mart.

Then they broke down what seemed to be signaling order and disorder at the most basic visual level.

"What came out is that the two strongest spacial predictors were the density, the sheer amount of curvy and broken edges or lines, and the extent of symmetry or asymmetry in the scene, with asymmetry relating to disorder," Kotabe says.

That coincides with (but doesn't necessarily require) agreed-upon visual distinctions of social disorder.

"When you actually imagine, literally, a broken window, it's changing the edge features, it's creating more broken edges," Kotabe says. "If you look at a crumbling building, there's going to be a lot more curvy edges as well as asymmetric features. No one's separated those physical features and isolated them from all of the social cues that are also present when these things come together in a meaningful way."

Then they set up a test, literally. Participants were given a tricky math test, and promised money for getting answers right. Next, they were shown various photos for five minutes, and asked to rate them as orderly or disorderly. Finally, the participants were told to grade themselves on the math test in order to get the money—giving them incentive to cheat.

Those who were shown disorderly photos were 26 percent more likely to cheat, and they cheated by 66 percent more than those who were shown orderly photos—meaning that not only were people more likely to cheat, but cheaters were likely to cheat more. But why?

One theory is that associations with physical disorder and rule-breaking are deep-seated.

"There's a rich literature on metaphorical thinking, and the idea that thought is shaped by mental metaphors," Kotabe says. "You can see some of these; some of these mental metaphors are manifested in our language. Interestingly, there seems to be a connection between rule-breaking, or following obligations and duty and so forth—what we call deontic concepts—and spacial features. We often say, in English, things like 'he's following the straight path,' 'he's breaking the rules,' 'he's bending the rules,' 'he's even-keeled.' It's interesting in this case that there seems to be a nice mapping-on of spatial features with rule-breaking concepts."

Another ties back to something I've written about before: the psychology of stress and scarcity and its impact on decision-making. Stress carries a cognitive load; a cognitive load lessens the ability one has to make the right decisions. If visual disorder requires more cognitive processing, it might follow that it lessens self-control.

"And self-control behavior is thought to underlie cheating behavior," Kotabe says.

It's an idea that has implications for how we make, and care for, the environment around us, getting order by creating it, starting with the most basic building blocks of our vision.