In the movie Judas and the Black Messiah, Fred Hampton gives a speech declaring that “Chicago’s the most segregated city in America. Not Shreveport. Not Birmingham. We’re here to change that: The Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and the Young Patriots are forming a Rainbow Coalition of oppressed brothers and sisters of every color.”

The African-American Black Panthers and the Latino Young Lords are well remembered for their roles in 1960s activism here. Less well remembered are the Young Patriots, a group of poor white Appalachian migrants that organized in Uptown. Hy Thurman, one of the Young Patriots’ founders, has just published a memoir of his protest days titled Revolutionary Hillbilly. Thurman, a Tennessee native who now lives in Alabama, spoke to Chicago magazine about his journey north, how he connected with the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, and the legacy of the Rainbow Coalition.

When and why did you come to Chicago from the South?

I came to Chicago in March of 1967. The reason I came was to escape some of the poverty in my hometown of Dayton, Tennessee, where they had the Scopes Monkey Trial. I was born into an impoverished family. We were sharecroppers. My father left when I was three months old. My mother had a third-grade education. There wasn’t financial help for the families like there is now, so you pretty much had to fend for yourself. Of course, we’d go work in the fields. I also wanted to get away from the stigma of being white trash in my hometown.

Why did so many Southern migrants move to Chicago and specifically to Uptown in the ’60s?

In the period of time, a lot of the coal mines were shut down. A lot of the farms were being taken over by big conglomerates and being mechanized. The textile mills were shutting down because of foreign trade. People were in poverty. People had to go somewhere. The most attractive route was going to the North. Uptown was a planned community. Back in the ’20s, it was planned to be an entertainment district by the city. Right after World War II, there was a big exodus to the suburban areas. There were big apartments that were cut up into smaller units, because the people that owned the building didn’t want to live in the area and they couldn’t sell the building. Not only people from the South, but it was a whole stirring pot for people from all over the world. My brother and I were paying $30 a week to live in a building on Sunnyside that was pretty well rat-infested, cockroach-infested. The heat wasn’t very good, and there certainly wasn’t any air conditioning.

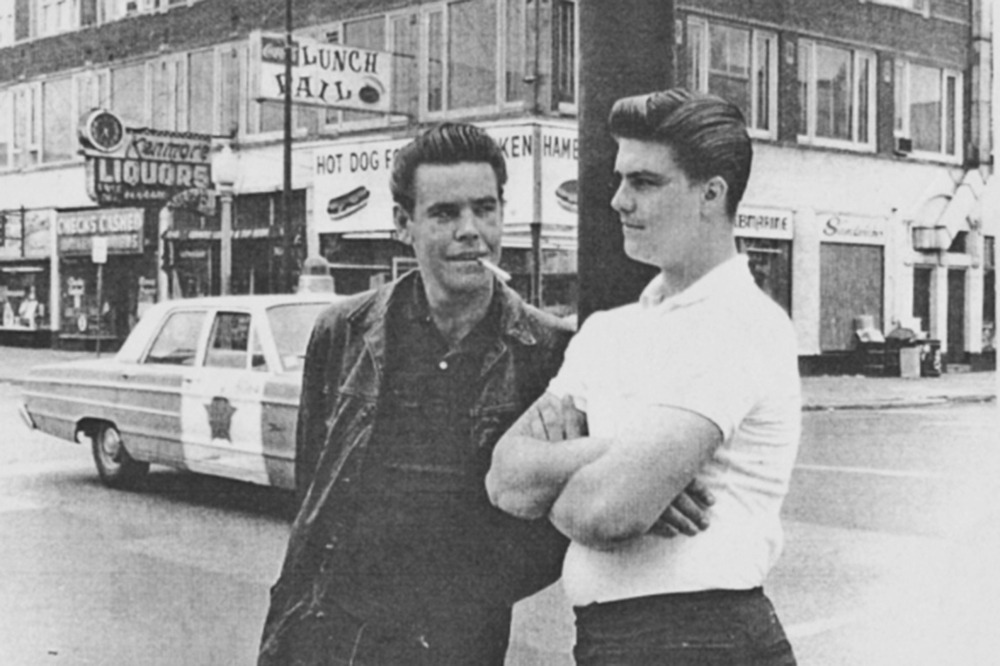

How were Southern migrants viewed in Uptown and by the rest of the city in that era?

Not very good. The rest of the city didn’t understand the Southern people, because of the stigma that was put on the hillbilly — being lazy. There was an article that came out in the Tribune, and of course that stereotype, the Southern white, was reinforced, and so it became even harder for people to get a job. They didn’t have a lot of skills to live in Chicago, either. Farming skills certainly weren’t needed. The ones that could get a job in the factories, some of them did very well, but not the biggest majority coming from the South. People were considered to be slow, lazy, and completely misunderstood.

What motivated the formation of the Young Patriots? What were the neighborhood issues you were organizing around?

We were organizing around housing issues, police brutality, urban renewal was a big one. We were organizing around health care, welfare. Some people couldn’t even get welfare. They were working out of day labor agencies that exploited the community and sent people to these very dangerous jobs, and you’d have to pay the managers of these agencies to work again. One of the things we were organizing against was racism. These communities in Chicago, the black and brown communities were in the shape as we were, and we began to get politically oriented through Students for a Democratic Society. We started as just street people hanging around and organizing. [Ed. note: Read this account of the Young Patriots’ effort to stop the displacement caused by Truman College by building a “Hank Williams Village” modeled on a Southern town.]

How did you connect with the Black Panthers and the Young Lords to form the Rainbow Coalition?

There’s a documentary called American Revolution 2. It shows where we met, in the Lake View community. There was a citizens’ group that would meet once a month at a church, they would bring in speakers. We were scheduled to talk to them, and there was a double booking that we didn’t know about: the Black Panthers were going to be there. This liberal, middle-class group came down on us very hard. Bobby Lee, who was with the Black Panthers, he stood up and defended us, that we were doing the same thing they were trying to do in their community. That was the first time he had heard of us. Bobby Lee went back to Fred Hampton, told Fred Hampton, “There’s these crazy hillbillies on the North Side, talking anti-racist stuff and revolution.” Hampton said, “This is what we need as far as unity in Chicago, breaking down these barriers of racism and segregation of communities.”

What were some of the actions that the three groups did together?

One of them was the takeover of the McCormick Theological Seminary with the Young Lords. The other was, we had had a peace demonstration at the Petrillo Bandshell. We did security with the Black Panthers, and there’s a picture that shows us shoulder to shoulder, us with our Confederate flag. The Rainbow Coalition was never meant to be an organization. Rainbow Coalition was just a code name for solidarity among all the colors. If the Black Panthers or the Young Lords would need us, we would go with them, and we would shed being a Young Patriot. We would become a Black Panther, we would become a Young Lord. Whatever they wanted us to do, we would do. Same thing if they were working with us.

Have you seen Judas and the Black Messiah? The Fred Hampton character mentions the Young Patriots at one point, although your group isn’t really portrayed. Were there people who were meant to be members of the Young Patriots in the movie?

No. They did not contact us at all. I’m glad the movie came out. It’s finally giving Fred Hampton and the Rainbow Coalition national recognition, but it didn’t go far enough. The FBI bad guy was the main character in the movie. The Young Patriots was not represented at all. When I found out they were making that movie, the only people I could get to was the Cleveland Film Board. I explained to them who I was—I was a Young Patriot, one of the co-founders of the Rainbow Coalition, and I needed to talk to somebody. They had already talked to the Panthers, and the Young Lords, but they never talked to us.

What do you think has been the Rainbow Coalition’s legacy in Chicago?

Oh, the legacy in Chicago is breaking down racial barriers for sure. At that time, all the communities were segregated. The legacy is what we did as a political platform together, organizing in solidarity, getting Bobby Rush elected to Congress, getting the first Black mayor elected, Harold Washington. He ran on the Rainbow politics. That brought a guy named Barack Obama to town. He and [David] Axelrod used the Rainbow Coalition concept on his [Senate] campaign. I think we changed politics forever in Chicago, and across the country.

Comments are closed.