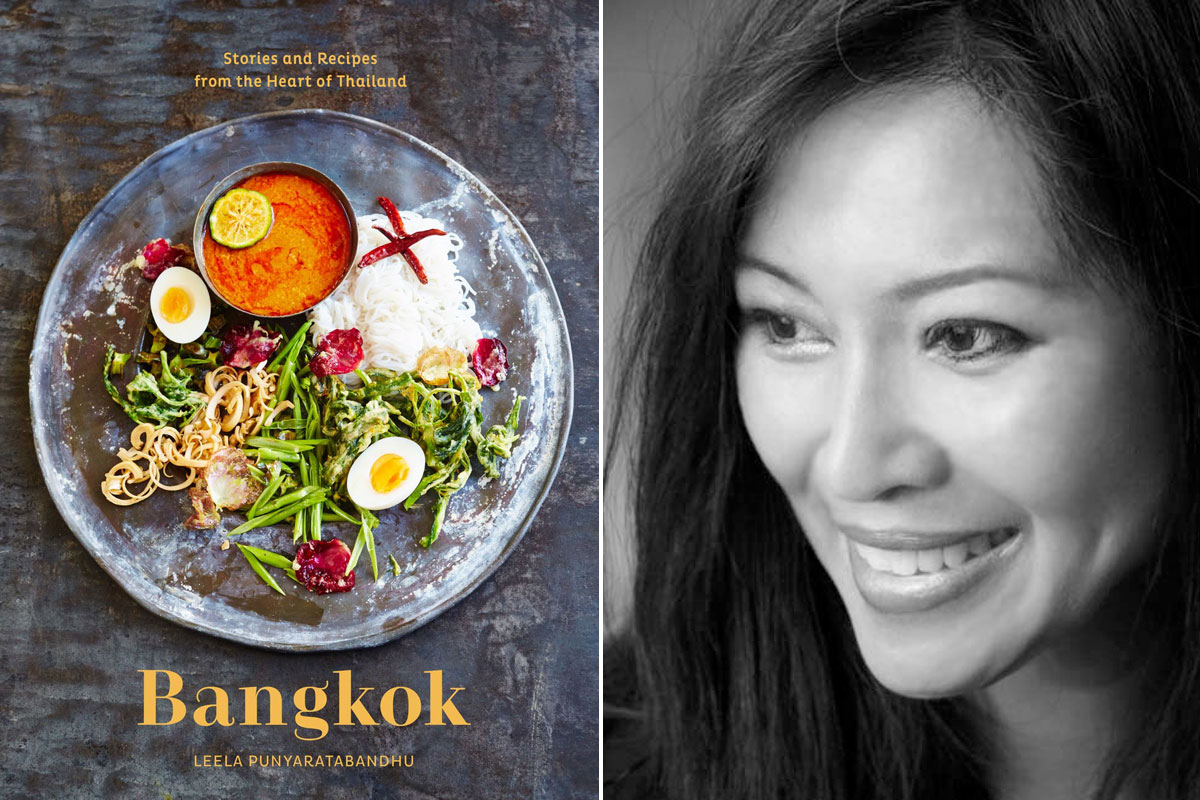

Not long after she debuted her Thai-food blog SheSimmers in 2008, my former Reader colleague Mike Sula introduced me to the work of food writer Leela Punyaratabandhu, a Bangkok native who divides her time between her hometown and Chicago.

I've been reading her ever since.

Her first book, Simple Thai Food: Classic Recipes from the Thai Kitchen, was a great addition to our library. Dishes familiar from American Thai restaurants with often-complex recipes and difficult-to-source ingredients were made doable for the beginner. Her second book, Bangkok: Recipes and Stories from the Heart of Thailand, is on the other side of the spectrum: faithful recipes representing the broad swath of the city's food, from traditional home cooking to famous restaurants to street carts to food stalls.

They're grounded in the many cultural origins of Bangkok cuisine: a dessert called golden threads is traced back to a Portuguese Japanese woman from the 17th century who created Thai-Portuguese desserts; there's a pork chop recipe in the style of the "cook shop," a hybrid Western/Chinese/Thai restaurant (which is served with slices of white bread and Worcestershire sauce); chicken and rice, Thai Muslim-style from Jio, a halal restaurant; fried rice from the menu of the early 20th-century Bangkok-to-Hua Hin train; a hot pot recipe modeled after a popular Cantonese hot-pot restaurant.

It's not just a cookbook; it's also a book about Bangkok's history and how the city's food emerges and evolves out of it. I spoke with her about how she came to write it, the history and current state of the Bangkok culinary scene, how Thai food is represented in America (and Chicago), and more. Hungry already? Below the Q&A we have a recipe from the cookbook for beef green curry.

Your cookbook is deeply grounded in the history, culture, and literature of Bangkok. And it sounds like your family was a powerful influence in that.

My family is a very traditional Thai family. My dad's side of the family can be traced back to an older Thai kingdom in the 1600s, which is when Siam, as it was known back then, opened itself to foreign trade and visitors. That's when my ancestors came from India to the court of the king. I had a long line of people from different cultures and races and languages. My mother's family's kind of like that.

We're a family that studies history, and we track out family of record, and collect books and recipes and things like that. We want to know where we came from, and why we are the way we are. My upbringing is kind of old-fashioned and ancient. The home that I grew up in used to be an embarrassment to me, because for a long time I thought we were poor. And I guess that we weren't—we just liked old stuff. There was nothing new and shiny and trendy or fashionable in our house at all. Everything that I'm able to do now I owe to that family tendency.

You wrote about an oven in your family's kitchen—a replica of an 1820s charcoal-fired oven that your great-grandmother grew up with.

That came from my maternal great-grandmother. She lived in an era when she could have gotten a regular oven imported from America or Britain. But she chose not to, believe it or not, because it was easier for her to use that type of ancient oven, where you're supposed to use hot coals underneath and on top.

My great-grandparents still lived in the era when electricity was something they tried to resist, and that's where my embarrassment came from—were we poor? Were we dumb? Were we backwards? It felt like they were preserving something that was about to die off. They wanted us to get to know how to work with coals, how to control the heat when you cook.

Did your family make a point to take you around the city trying new foods?

Not my family. They were kind of wrapped in their tradition. They had recipe books that were passed down from generation to generation and they would stick to those dishes. It's my generation that started eating out a lot more, trying new foods, things like that—the whole foodie culture. My great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents came from the time when home cooking was considered the best. All of the sudden we're glorifying street food, food made by other people, and I think if my parents were still alive, they would look at Instagram and shake their heads.

How did you get interested in this modern food culture?

It was generational, and it was part of the rebellion, too. Your parents would tell you, "Don't eat fresh vegetables on the street! They don't wash them! You don't know what you're eating!" Teachers, too: "Yesterday, somebody said this vendor used the bathroom by the tree, and he came back to his cart, not washing his hands!"

There used to be a derogatory term for a woman who didn't know how to cook or was too busy to cook—before she got home she'd buy food packed in little plastic bags—so my mother's generation was afraid they'd be called "plastic-bag housewives." But I grew up in a transition period. Women worked more, you didn't stay home to cook all day. This was a way to declare independence—I can eat out, you can call me a plastic-bag whatever, I don't care.

I ate out a lot, trying different things. I've come to the same conclusion, though—home cooking is the best. I came full circle.

What are the cook shops in Bangkok, and how did they contribute to the restaurant and food scene?

The cook shops were probably some of the first types of restaurants that we experienced in Bangkok. Before that it was all about home cooking. Then these Chinese cooks in Bangkok took what they learned from diplomats and businessmen from the West, and they combined Western food with their Chinese cooking skills, then added some Thai elements, and it became this interesting hybrid collection of dishes that we'd never heard of. This would be my grandparents' generation.

It sounds like, if there's an American equivalent, like a steak house or supper club.

Yeah. Although it's more international than that. It's a genre of its own. Don't go there and order steak that's rare or medium-rare; they'll just look at you like, are you stupid. It's just a piece of meat, well done, cooked to death, and tomatoes and cucumber and onions and green lettuce, and some simple vinaigrette, served by very old Chinese Thai women who don't know anything about customer service and they don't care. They use an abacus to tally up the bill. It's like a museum.

What's the Bangkok restaurant scene like now? You mention that it's kind of in a retro phase.

You see a lot of restaurants popping up in the last 10 years that are run by younger people, 25 through 35, who weren't interested in anything culinary before, but they all of a sudden started collecting old cookbooks from over a century ago. People with long traditions of family recipe collections, they got interested in what their grandmothers used to tell them (and they didn't listen to before).

The political climate in Bangkok and Thailand has been sort of unstable for the past 10 years. There is a growing demand from people from upcountry who want elections and full democracy. The retro trend is almost like the middle class is yearning for the time when [the rural class] didn't demand anything different, to be heard, to be equal. You can look at it that way. But if you look at it in a more positive way, it's people missing the time when things were peaceful to them—eating food like that reminds you of home, of your roots. There's an unspoken feeling that Bangkok isn't what it used to be anymore. We have been fighting too much; street protests and all that.

There seems to be a competition among these retro restaurants about who can go back the furthest, closest to that time when cookbooks were first published about 100 years ago.

For you, personally, why do you like home cooking the best?

Because that's the way our culture is. Home cooking is the foundation of everything. If you come to Bangkok, and you ask me where you should go eat, I would probably recommend a restaurant that I consider good. And if you ask me why I consider the restaurant good, they make the kind of food that is the closest to what you would have gotten in a Thai household.

Bangkok is not known for street food, not among the locals. I still find it surprising that we glorify street food so much, to the point where, when the news of Bangkok street food being at risk got out to the world, everyone panicked, as if the whole city would collapse. [The situation around Bangkok street food right now is complicated, but she explained the situation for CNN.] Is this better than home cooking? No, and everybody knows that—not the food writers that come here for a week and go back, though.

In terms of Thai restaurants in the United States, how do they represent Thai food as it is in Thailand?

It used to frustrate me when Thai restaurants didn't do things I thought they should do. I came to understand that it's easier for me to criticize, not having to pay rent at the end of the month, not having to watch things get thrown out that people don't eat. The truth is they don't see themselves as the ambassadors of Thai cuisine or culture. The bottom line is that they have to make a living. That's what determines what they put on a menu.

It's not about "let's present Thailand as it really is." That's only possible for a chef who comes from a privileged background, when you're so good with English that you can communicate with people, talk to the press, and be looked upon as the top chef of Thai cooking. Mom and pop Thai restaurants, I feel for them; they don't have that luxury.

In the end, American Thai restaurants have a very eclectic menu full of things you'd never see under the same roof in Thailand. You get one dish from markets in the Northern region; you have a royal Thai dish from the heart of Bangkok served to rich families; you see a Chinese dish that's only made in Chinatown and nowhere else in Bangkok. You see a hodgepodge of things that don't belong together at all, but they belong on this menu because Americans love them.

How did you decide to follow up Simple Thai Food with Bangkok?

Simple Thai Food is constructed in the same way that a typical Thai restaurant menu in the U.S. is constructed, which is artificially, in the sense that it's a collection of things that Americans already know. The Bangkok cookbook is a collection of recipes that have evolved along with the city, organically, influenced by all its cultures in the past 200 years. I feel the responsibility of not watering that down, because it's supposed to represent the soul of the city. So, yeah. 25 ingredients in one curry! Most of the dry ingredients can be found online, but the fresh stuff, like herbs, you kind of have to live in a larger city like Chicago.

What do you think of the Thai food in Chicago?

I think it's awesome. What I love about the Thai food scene in Chicago is that there's something unpretentious about it. They tend to gravitate toward home-type foods, but they don't present themselves as completely regional. Sticky Rice (4018 N. Western Ave.) is an exception, but they sell other things, too. It represents the Midwestern mentality: "Whatever I make at home, that's what I put on the menu." A place like Immm Rice & Beyond (4949 N. Broadway), that's the kind of stuff that an office worker in the Bangkok business district would eat during the lunch hour—you would walk into a place like Immm and grab a plate of rice with two types of curry.

In the book, you mention two recipes that would be your choices for a last meal: poached chicken and rice with soy-ginger sauce, and grilled chicken with sticky rice. Why those?

The first one, poached chicken and rice—the only way you could be exposed to it was that you ate out, because it was made mostly by Hainanese Chinese immigrants back then. That was the first thing I remember eating outside the home, and it was with my dad, who died when I was a kid. He loved it, too, so he took me there all the time. It was a nostalgic thing for me. When you love the person that you ate something with, that thing became more delicious. I can't explain it. And it tastes good! If you come to Bangkok and you ask me what you should eat, I would recommend that, because it's like the easiest thing to eat, it's not spicy. Chicken and rice, everyone loves that.

The other one, grilled chicken and sticky rice… it just tastes good. Sticky rice and grilled chicken is easy and unpretentious. Notice the absence of vegetables or anything good for you. Give me my chicken and my carbs and I'm set.

Beef Green Curry (kaeng khiao wan nuea)

By Leela Punyaratabandhu

Here is the most satisfying and delicious beef green curry I’ve ever made.It’s thicker than most versions, with just enough sauce to coat the meat—khluk khlik, as a Thai would say—and it is heavier on cumin. It has no vegetables—not even eggplants, allowing the beef to take center stage with the fragrance of the paste and the sweet, creamy coconut milk sharing the spotlight. The only perfuming herb is bruised and torn makrut lime leaves. Although the curry is intensely green it isn’t very hot, as the veins of the chiles have been removed. But then I top it with fresh green chiles, vibrant and fragrant, reinforcing the fresh chiles in the paste as well as ratcheting up the heat. Finally, I drizzle some fresh coconut cream on top. This is beef green curry at its best.

Ingredients

Curry Paste

- 1 tablespoon coriander seeds

- 1 tablespoon cumin seeds

- 1 teaspoon white peppercorns

- 1 teaspoon coarse salt (omit if using a food processor)

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped galangal

- 1 tablespoon paper-thin lemongrass slices

- 1 teaspoon finely chopped makrut lime rind

- 1/2-inch piece turmeric root or 1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1 teaspoon packed Thai shrimp paste

- 5 fresh green Thai long chiles, deveined and coarsely chopped

- 7 fresh green bird's eye chiles

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped cilantro roots or stems

- 5 large cloves garlic

- 1/4 cup sliced shallots, cut against the grain

Curry

- 1/2 cup freshly extracted coconut cream, or 1/2 cup canned coconut cream plus 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

- 1/2 cup coconut milk

- 2 pounds untrimmed boneless well-marbled chuck steak or rib-eye steak, thinly sliced against the grain on a 40-degree angle into bite-sized pieces

- 2 teaspoons fish sauce, or as needed

- 1 teaspoon packed grated palm sugar, or as needed

- 4 makrut lime leaves, lightly bruised and torn into small pieces

- Fresh green Thai long or bird's eye chiles, stemmed and halved lengthwise

- 1/4 cup packed Thai sweet basil leaves

Topping

- 1/4 cup coconut cream

Directions

To make the curry paste, in a small frying pan, toast the coriander and cumin over medium heat, stirring constantly, until fragrant, about 2 minutes. Transfer to a mortar, add the peppercorns, and grind to a fine powder. Add the salt, then, one at a time, add the galangal, lemongrass, lime rind, turmeric, shrimp paste, chiles, cilantro, garlic, and shallots, grinding to a smooth paste after each addition.

(Alternatively, combine all of the ingredients except the salt in a food processor and grind to a smooth paste.)

To make the curry, put the paste and coconut cream in a 4-quart sauce pan, set over medium-high heat, and stir until the fat separates and you can smell the dried spices, 1 to 2 minutes. Add the beef, the coconut milk, fish sauce, and sugar, stir well, cover, turn the heat to medium, and cook until the beef is no longer pink, 7 to 8 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasoning with more fish sauce and/or sugar if needed. Check the consistency and amount of the sauce and add water if needed. For this curry, I like just enough sauce to coat the meat—like pot roast. Stir in the lime leaves, fresh chiles, and basil leaves.

The curry can be transferred to a serving dish and served right away with rice, or it can be cooled, covered, and refrigerated overnight and then reheated the next day (the flavor will be even better). When you serve the curry, top it with the coconut cream.

Reprinted with permission from Bangkok by Leela Punyaratabandhu, copyright 2017. Photography by David Loftus. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.